Article reviewed by: Dr. Sturz Ciprian, Dr. Tîlvescu Cătălin and Dr. Alina Vasile

Article updated on: 22-05-2025

Knee bone edema – what it is, causes, symptoms and treatment

- What is knee bone edema?

- Classification of bone edema

- Symptoms of bone edema in the knee

- Diagnosis and investigations

- Treatment of knee bone edema

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in treating knee bone edema

- How you can prevent knee bone edema occurrence

When receiving an MRI result that mentions "bone edema" in the knee, many patients wonder what this diagnosis means and how serious it is. Knee bone edema, also known as bone marrow edema, represents an accumulation of fluid and inflammation inside the bone, specifically in the bone marrow space. This change is visible especially on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and often signals suffering of the subchondral bone (the portion of bone under the cartilage).

The good news is that bone edema is often a self-limiting condition, meaning it can improve on its own, but it still requires medical evaluation and sometimes treatment, especially due to associated pain.

What is knee bone edema?

Bone edema represents abnormal fluid accumulation inside the bone, in the bone marrow. Practically, affected areas appear on MRI as more whitish "spots" (hyperintense) in bone, a sign that bone tissue is congested with fluid and blood, usually following microtrauma or inflammation. It's important to remember that bone edema is not the same as ordinary soft tissue edema (swelling at skin or muscle level); in the case of bone marrow edema, fluid accumulates in the internal spaces of the bone and doesn't always produce visible external swelling. The term may sound worrying, but it describes more of an imaging sign than a disease itself. In other words, bone edema is an MRI finding indicating the existence of a lesion or stress at bone level, having various causes that we will discuss immediately.

Knee bone edema occurs, therefore, when the bone in the knee component (femur, tibia, or patella) suffers a disturbance, such as mechanical shock, temporary decrease in blood circulation, or inflammation – and as a response, fluid gathers in that area of bone marrow. This change is relatively frequently encountered at lower limb joint level (hip, knee, ankle) and can often go unnoticed clinically, being discovered accidentally on routine MRI. However, depending on cause and extent, bone edema can cause intense pain and movement limitation.

Classification of bone edema

Doctors often divide bone edemas into two categories: primary bone edema (also known as idiopathic medullary edema syndrome, which appears without an apparent cause) and secondary bone edema, which results from another preexisting condition or lesion. Regardless of type, it's essential for a specialist to correctly assess the situation, as edema itself can be a sign of an underlying problem requiring treatment (for example a microfracture, contusion, or onset of osteonecrosis).

Primary bone edema (idiopathic medullary edema syndrome)

Primary bone edema is a rare condition where pain and edema appear in bone marrow without a clear identified cause (there is no fracture, advanced arthrosis, or other obvious disease). This syndrome is sometimes called transitory osteoporosis or transient medullary edema, because it has the characteristic of spontaneous remission after a period of time. It predominantly affects lower limbs and was initially described in pregnant women in the third trimester and middle-aged men.

In fact, statistics show that medullary edema syndrome (primary) appears in 98% of cases at lower limb bone level and much more rarely at upper limb level. Men between 30–60 years old are more predisposed (in a ratio of about 3:1 compared to women) and young women (20–40 years old), as well as pregnant women, as we mentioned.

Why does it occur? The causes are not fully known, but some studies have associated this condition with metabolic disorders (for example vitamin D deficiency) or vascular factors (deficient circulation, local microthromboses). Essentially, the affected bone goes through an episode of temporary density loss and fluid accumulation, which causes pain. The good news is that primary bone edema has a transitory character: classically, it evolves in three clinical phases:

- first month: initial pain and limb function limitation;

- next 1–2 months: pain worsens and reaches a maximum;

- after 3–6 months: symptoms begin to improve gradually and edema usually resolves completely.

This spontaneously favorable evolution doesn't mean the patient must suffer during all this time, symptomatic treatments (for pain) and supportive ones can hasten recovery and improve quality of life, as we will see. Correct diagnosis is also important, to exclude other more serious causes that can mimic bone edema syndrome.

Secondary bone edema (known causes)

Much more commonly encountered is secondary bone edema, meaning that which appears as a result of another problem. Bone edema itself, in this context, is a symptom or consequence of an underlying lesion or disease. We will detail below the most frequent causes and risk factors that can lead to knee bone edema occurrence:

Knee trauma and contusions

Direct blows or falls on the knee can produce so-called bone contusions (also known as bone bruise). These are trabecular microfractures inside the bone, which don't appear on X-ray, but are visible on MRI as bone edema. For example, in severe sports injuries, such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture, such bone contusions frequently appear through violent impact of bones against each other. Studies show that in approximately 80% of anterior cruciate ligament rupture cases, bone contusions/edemas are identified on MRI at knee level. The presence of this post-traumatic edema is associated with more intense pain in the first weeks after accident and can predispose the knee to post-traumatic arthritis development if bone lesion is severe. In the absence of other complications, bone contusions tend to heal in a few months, with bone gradually regenerating.

Overuse and stress microfractures

Intense physical activities, especially those involving jumping, running on hard terrain, or lifting heavy weights, can lead to repetitive microtrauma in bone structure. Thus appear stress fractures – very fine cracks in bone, which initially may go unnoticed on X-rays. A bone constantly subjected to pressure without sufficient recovery time can develop edema at bone marrow level, as a sign of this overuse. At knee level, athletes such as marathon runners, basketball players, or football players may present bone edemas in femoral condyles or tibial plateau due to repetitive impact. Biomechanical factors also play a role. For example, defective alignment of the lower limb (genu varum or valgum) can put extra stress on a certain portion of the knee, leading over time to subchondral bone edema in the overused compartment. Osteochondritis dissecans, a condition where a small fragment of bone and cartilage begins to separate from healthy bone, can also be preceded by local bone edema.

Degenerative diseases – knee arthrosis:

Osteoarthritis (gonarthrosis) is a very frequent cause of subchondral bone edema. As articular cartilage wears out, mechanical loading on the underlying bone increases, and bone reacts through remodeling and micro-fractures, with edema appearing in bone marrow. The presence of bone edema in arthrosis usually indicates an active and painful disease. Studies have shown that bone edema lesions on MRI appear in a significant percentage of patients with symptomatic knee arthrosis – in a study of 223 patients, approximately 33% had subchondral bone edema visible on MRI. The importance of this fact is major: bone edema in arthrosis is considered a strong risk factor for disease progression. According to data, 36% of knees with medial bone edema (in the internal knee area) presented radiological worsening of arthrosis (joint space narrowing) in an interval of 15-30 months, compared to only 8% of knees without edema.

In other words, the presence of subchondral edema increases the risk of subsequent structural joint deterioration by about 6.5 times. Bone edema partially explains why some patients with gonarthrosis have much greater pain than what would be anticipated looking only at their X-ray, it's a sign of active inflammation in bone. For this reason, severe arthrosis treatment also includes addressing these lesions (through a combination of anti-inflammatories, infiltrations, or other therapies meant to reduce subchondral inflammation).

Osteonecrosis (avascular necrosis)

Spontaneous knee osteonecrosis (abbreviated SONK in English literature) is a condition where a small portion of femoral bone, usually the medial condyle, suddenly loses its blood supply, leading to bone tissue death. It frequently appears in women over 50–60 years old and manifests through intense pain, without obvious trauma. The first sign on MRI is diffuse bone edema in the affected area, indicating an incipient, still reversible stage. Rapid treatment – weight unloading, bisphosphonates, hyperbaric therapy – can prevent bone collapse. If ignored, the lesion evolves toward subchondral fracture and bone collapse, requiring surgical intervention. There are also secondary forms, in younger people, associated with risk factors such as alcohol or steroids, but these mainly affect the hip. Rarely, osteonecrosis can appear after knee arthroscopies, and persistent postoperative pain must be investigated through MRI.

Inflammatory arthritis

Rheumatological conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or psoriatic arthritis can present bone edema at involved joint level, including the knee. In rheumatoid arthritis, for example, MRI can show edema in bone underlying cartilage even before bone erosions are visible. This edema reflects intense inflammation of synovial membrane and bone and often predicts bone erosion appearance (holes in bone) over time, if disease is not well controlled. In other words, in inflammatory arthritis, bone edema is a marker of disease activity and destructive potential on the joint. Aggressive treatment with disease-modifying drugs (DMARDs, including biologics) aims to reduce inflammation and, implicitly, bone edema to protect joints.

Bone infections (osteomyelitis)

Bone infection can cause severe edema and inflammation in bone marrow. Knee osteomyelitis (actually of bone extremities composing the knee) is rare, but can appear in the context of an open wound, surgical intervention, or hematogenously (bacteria reached through blood). Diffuse bone edema on MRI, associated with fever and infection markers in blood, can indicate osteomyelitis, which requires aggressive antibiotic treatment and sometimes surgical curettage. In such cases, edema is not the problem itself, but the infection causing it.

Bone tumors

Both benign and malignant bone tumors or bone metastases can cause edema in surrounding bone. For example, a chondrosarcoma or metastasis at distal femur level can present on MRI a "halo" of bone edema around the tumor area, due to bone reaction to abnormal growth. It must be emphasized that the vast majority of knee bone edemas do NOT represent tumors. However, the radiologist doctor carefully analyzes MRI images to exclude this possibility – sometimes by recommending an additional examination (for example, CT or even biopsy if suspicions arise). Fortunately, cases where bone edema proves to be a malignant tumor lesion are extremely rare. If such suspicion exists, additional investigations will be promptly indicated for a certain diagnosis.

Symptoms of bone edema in the knee

Deep knee pain is the main symptom of bone edema. Interestingly, bone edema can exist without symptoms, especially if it's small or appears in less active people. That's why it's sometimes discovered accidentally on an MRI performed for another reason. However, when it produces symptoms, these tend to be quite intense. Bone pain caused by edema can be present both during movement and at rest, and is often severe enough to limit affected limb functionality.

Patients often describe deep, persistent pain, felt "inside" the knee, different from superficial soft tissue pain. It can be aggravated by weight bearing on the respective foot, effort (climbing stairs, prolonged walking), or even standing for a long time. In some cases, pain is present at night or in the morning, being able to wake the patient from sleep or cause brief morning stiffness.

Visible swelling (edema) at the knee is not always present in bone edema, because, as we explained, fluid is inside the bone and not in soft tissues. However, if bone edema is massive, it can induce an inflammatory reaction in bone and joint, leading to joint effusion (fluid in joint) and knee swelling. The patient can then notice increased knee volume, with tight and shiny skin, sometimes warm to touch. However, joint effusion is not a constant symptom in bone edema syndrome and appears more rarely, especially in primary medullary edemas, joint space remains intact and without excess fluid. Therefore, the presence or absence of swelling depends much on edema cause: in inflammatory arthritis or arthrosis, it's possible to coexist with joint effusion; in isolated bone contusions, the knee may have normal external appearance.

Also, pain generated by bone edema can make normal knee use difficult. The patient may limp due to weight-bearing pain, have difficulties climbing and descending stairs, cannot kneel or squat, and feels the knee weakened. Sometimes, bone edema (especially if post-traumatic) can also cause a sensation of instability or knee "giving way," because pain prevents the patient from properly coordinating the limb. In situations where edema is associated with structural lesions (for example a stress fracture), inability to bear weight on the respective foot may also exist.

It's important to note that symptom severity doesn't always correlate directly with cause severity. For example, primary bone edema (without permanent lesions) can cause atrocious pain for several months, then disappear without trace. Conversely, modest edema caused by a small tumor lesion might not hurt at all in incipient phases. Therefore, medical evaluation is essential to establish exact diagnosis.

Diagnosis and investigations

Bone edema diagnosis is made mainly with the help of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is the investigation of choice because it can visualize in detail changes inside the bone, unlike standard X-ray, which only shows bone cortical structure and any larger fractures. On MRI, bone edema appears as an area with increased signal on special sequences (STIR or T2 fat sat), indicating fluid presence. Additionally, MRI helps identify edema cause – for example, it can show ligament rupture, cartilage lesion, occult fracture, or other associated anomalies.

Besides MRI, sometimes knee X-rays are also performed – these cannot directly visualize edema, but can show changes such as joint space loss (in arthrosis), possible fractures or bone collapse (in osteonecrosis), or erosions (in rheumatoid arthritis). X-ray is useful especially to exclude other obvious bone pathologies and to have a structural reference point.

Computed tomography (CT) can be recommended in situations where subchondral fracture is suspected (for example in osteonecrosis or stress fractures), because CT visualizes bone details very well. However, CT doesn't show edema; it's complementary to MRI, not a replacement.

Bone scintigraphy or PET-CT investigations can sometimes be used when searching for metastatic lesions or when diagnosis is unclear. Bone edema, being a metabolically "active" lesion, will uptake on scintigraphy, but this examination is not specific (many other bone problems uptake radiotracers).

In some special cases, if infection is suspected, blood tests can be done (inflammation markers such as ESR, C-reactive protein) or even bone biopsy (taking a small bone cylinder for histopathological analysis). Biopsy is needed extremely rarely, only if the doctor wants to exclude tumor infiltration or chronic bone infection that can mimic banal edema.

Therefore, the key to diagnosis is correlating imaging results (especially MRI) with clinical context. An experienced orthopedist or sports medicine doctor or rheumatologist will be able, based on MRI image and clinical examination, to determine the probable cause of edema and initiate appropriate treatment.

Treatment of knee bone edema

In bone edema treatment, two main objectives are pursued: symptom amelioration (especially pain) and treating the underlying cause to allow bone healing and prevent complications. The therapeutic approach depends much on the identified cause and symptom severity. We will detail treatment options, from conservative measures to modern therapies, including hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Conservative measures and pain management

In many cases, knee bone edema is a self-limiting condition that will resolve over time, so initial treatment is conservative. Rest and reduced loading on the knee joint are crucial. The doctor may recommend removing weight bearing from the affected foot for 3–6 weeks (for example, using crutches or braces that unload weight from the knee). This gives the bone a chance to recover without additional mechanical stress.

Also, analgesic and anti-inflammatory medication plays an important role: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, diclofenac, or meloxicam can reduce pain and local inflammation. Depending on pain intensity, simple analgesics (paracetamol) can be associated or, short-term, even mild opioids, at doctor's recommendation. For stomach protection, if taking NSAIDs, the doctor may indicate a proton pump inhibitor. Local measures, such as ice applied to the knee (local cryotherapy), 15 minutes several times a day, can help diminish inflammation and pain. Also, elevating the lower limb on a higher plane and wearing an elastic knee brace can offer support and reduce peripheral edema.

Physiotherapy and rehabilitation

After the acute pain phase, once it subsides somewhat, medical recovery is very important. Personalized physiotherapy exercises maintain knee joint mobility and surrounding muscle tone (quadriceps, hamstrings), thus preventing stiffness and muscle atrophy. A physiotherapist can show you gentle flexion-extension movements without loading, closed kinetic chain exercises (such as quadriceps contraction with leg extended) and light stretching. The goal is that, as bone heals, the knee doesn't completely lose function.

Kinesiotherapy will be done progressively, avoiding pain – if a movement causes sharp pain, it must be stopped. Adjuvant physical therapy techniques can also be used: electrotherapy (TENS) for pain relief, ultrasounds and laser therapy can help accelerate healing by stimulating microcirculation. A more recently appeared method is diamagnetic therapy (using a powerful pulsating magnetic field to "push" edema from bone toward return circulation), about which some clinics claim helps faster edema resorption.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT)

This therapy is another procedure used in musculoskeletal lesions – practically, high-energy acoustic pulses applied locally. In bone edema cases (especially in incipient stages of osteonecrosis or contusions), clinical studies suggest that ESWT can reduce pain and edema by stimulating bone repair. For example, in femoral head osteonecrosis (a condition similar in mechanism to knee osteonecrosis), it was observed that shock wave therapy helps diminish medullary edema and symptom amelioration, being a valuable non-invasive alternative.

In advanced recovery clinics, such as Hyperbarium, such modern procedures – laser, shock waves, integral cryotherapy, etc. – can be combined in a treatment protocol meant to hasten healing.

Pharmacological treatment of underlying cause

If bone edema is caused by a certain condition, then treating that cause is essential. In arthrosis, for instance, intra-articular infiltrations with hyaluronic acid (viscosupplementation) can be used to ameliorate symptoms and maybe even reduce subchondral stress, or corticosteroid infiltrations to calm intense acute inflammation (although their effect is temporary).

In incipient knee osteonecrosis, some studies have shown benefits through bisphosphonate administration (medications that combat bone mass loss, such as alendronate or zoledronate). A study highlighted that combined use of alendronate and zoledronic acid reduced bone edema and pain in patients with spontaneous knee osteonecrosis, offering a new medical treatment perspective for this condition.

In idiopathic primary bone edema, small doses of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) have been successfully used, which, besides anti-inflammatory effect, can improve bone microcirculation, and, as we will see below, hyperbaric oxygen therapy associated with bisphosphonates and rest led to faster healing. For inflammatory arthritis, background treatment (for example methotrexate, anti-TNF, or other biological therapies in rheumatoid arthritis) will reduce systemic inflammation and, implicitly, articular bone edema, preventing deterioration.

Surgical interventions in bone edema

In most bone edema cases, surgical intervention is not needed. However, if we're dealing with a mechanical lesion underlying the edema, surgery may be necessary. For example, bone edema caused by a complex meniscus tear with fragment caught between articular surfaces might require arthroscopy for meniscectomy (fragment removal) and thus elimination of underlying stress source.

In osteonecrosis, if it's in an advanced stage (but still localized), decompressive drilling can be performed – a minimally invasive orthopedic procedure where one or more small holes are made in affected bone, to decrease intraosseous pressure and stimulate new blood vessel formation. This decompression reduces edema and pain and can prevent subsequent collapse of necrotic bone.

In the unfortunate situation where edema is associated with a tumor lesion, of course, treatment will be oncological (excision, curettage, reconstruction, etc., depending on diagnosis). And in very advanced arthrosis, if bone edema is just part of extensive articular destruction, knee prosthesis (total arthroplasty) can be the definitive solution that will eliminate pain, replacing worn joint with an artificial one. It's however an ultimate measure, reserved for severe cases, after conservative options have been exhausted.

In recent years, adjuvant therapies meant to accelerate bone edema healing and ameliorate pain present special interest, one of these being hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

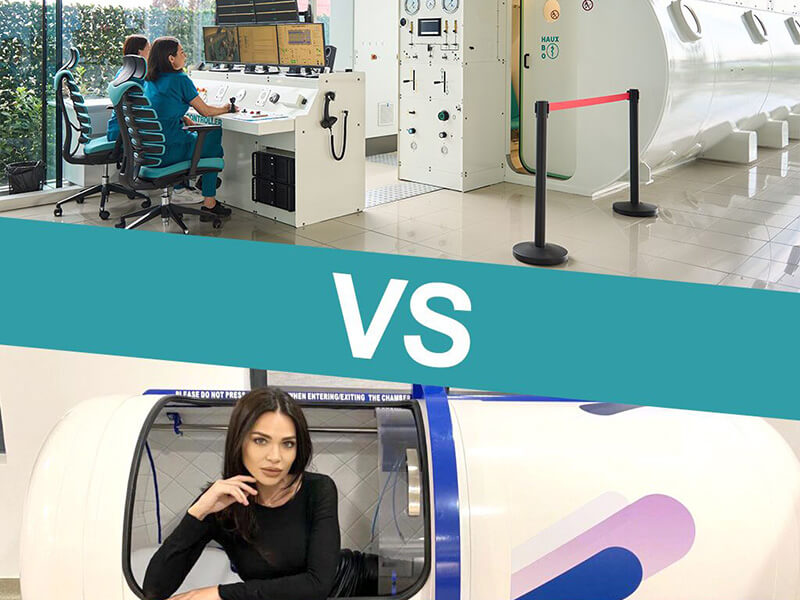

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in treating knee bone edema

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (abbreviated HBOT, from Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy) consists of breathing pure oxygen at high pressure, in a special enclosure called a barochamber. Practically, the patient is introduced into a sealed chamber where atmospheric pressure is increased (for example to the equivalent of 2-3 atmospheres), and through mask or ambient breathes 100% pure oxygen. Under these conditions, the amount of oxygen dissolved in blood and body fluids increases tens of times above normal, allowing oxygen to diffuse much deeper into tissues, even in areas with deficient circulation.

Hyperbaric therapy is an accredited medical treatment, already used in multiple indications: from acute diseases (such as carbon monoxide poisoning, diver decompression sickness, severe infections like gas gangrene) to chronic conditions (difficult wounds, diabetic foot, chronic osteomyelitis, bone radionecrosis, adjuvant in treating some ischemias, etc.).

In the context of bone edema and orthopedic lesions, the rationale for using hyperbaric oxygen is to stimulate bone healing processes: supplementary oxygen helps new blood vessel formation (angiogenesis), reduces edema and inflammation, and stimulates osteoblast activity (cells that form bone). It also has a bactericidal effect (killing bacteria) and increases activity of cells that "clean" deteriorated tissue.

For knee bone edema, hyperbaric therapy is used especially in cases where evolution is prolonged or edema cause is difficult to treat through conventional methods. A typical example is primary bone edema syndrome (idiopathic) and incipient avascular osteonecrosis. In these situations, hyperbaric oxygen therapy is usually applied in daily sessions (each session lasts approximately 120 minutes), a complete cure totaling around 20–40 sessions, depending on severity and patient response. During sessions, patients are monitored, therapy being painless – they just need to breathe and relax, while increased pressure and medical oxygen have their effect.

The effectiveness of hyperbaric therapy in knee bone edema has been studied by researchers, and results are more than encouraging. A study published in 2023 evaluated HBOT in patients with knee medullary edema, comparing a group that received hyperbaric therapy with a group that didn't (all patients also benefiting from standard treatment with medications like alendronate and unloading rest). Conclusions showed that hyperbaric oxygen therapy is an effective treatment option for bone marrow edema, leading to faster healing of lesions shown on MRI and more prompt pain amelioration. Additionally, treatment was well tolerated, with no significant adverse effects noted in the study.

In other words, patients who underwent hyperbaric therapy sessions recovered much faster compared to those who followed only conventional treatment. Another benefit of hyperbaric oxygen, hard to quantify in numbers but reported by clinicians, is that it reduces edema and inflammation in a systemic way – which can be useful especially when bone edema is diffuse or when the patient has other affected tissues (for example muscles, cartilage).

Besides the mentioned study, hyperbaric oxygen therapy action mechanisms support its use: increased oxygen tension in bone leads to better quality bone tissue formation and decreased intraosseous pressure (through edema reduction). Practically, hyperbaric oxygen breaks the vicious circle of bone edema, where accumulated fluid produces pressure and ischemia, perpetuating the lesion. In hyperbaric environment, this ischemia is counteracted, allowing bone tissue to regenerate. Of course, hyperbaric therapy doesn't replace other treatments, but adds to them. The patient will continue to follow other recommendations (rest, medications, etc.), and hyperbaric therapy comes as a healing process accelerator.

It's important to know that not every hospital or clinic has access to a barochamber, as this requires special infrastructure. In Romania, accredited centers for hyperbaric therapy are still very few, and the Hyperbarium clinic in Oradea is among them, being dedicated exclusively to hyperbaric medicine and advanced recovery therapies. For patients with knee bone edema who don't respond to usual treatments or who want to optimize their chances of rapid healing, a consultation for hyperbaric therapy can be of great help. Like any medical procedure, HBOT also has contraindications (for example, certain pulmonary conditions, untreated ear trauma, pneumothorax, etc.), but these are relatively rare and, overall, therapy is safe under medical staff supervision.

In conclusion, hyperbaric oxygen therapy has proven to be a valuable ally in bone edema treatment, especially in combination with other methods. It can hasten healing, can reduce pain, and can even prevent the need for invasive interventions, offering patients a chance for faster and more complete recovery.

How you can prevent knee bone edema occurrence

Although bone edema is, in many cases, a consequence of unpredictable factors, such as trauma or degenerative diseases, there are simple and efficient measures you can take to reduce the risk of this condition occurring or to prevent recurrence after a previous episode. Prevention doesn't just mean avoiding pain, but also maintaining mobility and quality of life long-term.

The first step is protecting knees from overuse. If you practice impact sports (football, basketball, running on asphalt), choose footwear with shock-absorbing soles and alternate intense training with recovery days. Add thigh muscle strengthening exercises (quadriceps and hamstrings) to your program, which help knee stabilization and reduce pressure on subchondral bone. Avoid sudden movements or pivoting on hard terrain, and if you've had previous injuries, wear braces or compression bandages for additional support.

Another important factor is body weight control. Excess weight significantly increases pressure on knee joints, especially when climbing stairs or walking uphill. According to a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatism, every 5 extra kilograms increases the risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis by up to 36%. A balanced diet, moderate physical activity, and regular medical consultations for weight monitoring can have considerable impact on joint health.

Don't neglect the role of vitamins and minerals either. Low levels of vitamin D and calcium can affect bone density and can increase susceptibility to bone edema, especially in older people. Discuss with your doctor about routine analyses for vitamin D, especially in cold months, and about any necessary supplements. Also, proper hydration and avoiding excesses (alcohol, smoking) support healthy bone metabolism.

For those who already have joint conditions (arthrosis, rheumatism), periodic monitoring through MRI or other investigations recommended by the doctor can help early identification of bone changes. In case of persistent or unexplained pain, a thorough orthopedic consultation is essential to prevent worsening.

If you've already gone through a bone edema episode, it's recommended to strictly follow the recovery program, continue maintenance exercises, and periodically return for medical evaluations. Pay attention to your body's signals – pain that doesn't go away, stiffness, or instability sensation shouldn't be ignored. With a balanced lifestyle, medical education, and support from a specialist team, you can significantly reduce the risk of bone edema recurrence and can take long-term care of your knee health.

In conclusion, knee bone edema can be a painful and worrying condition, but with correct diagnosis and adequate treatment plan, most patients recover completely. Modern technologies such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy, available at specialty clinics like Hyperbarium clinic, offer additional solutions for difficult cases, hastening healing and ameliorating suffering. If you're facing knee pain and have been diagnosed with bone edema, don't hesitate to seek specialist advice and explore treatment options – rapid recovery and return to normal life are perfectly achievable goals today, with the help of cutting-edge therapeutic approaches.