Article reviewed by: Dr. Sturz Ciprian, Dr. Tîlvescu Cătălin and Dr. Alina Vasile

History of hyperbaric therapy

In a fascinating journey through time, our article opens the pages of history to explore the origins and evolution of hyperbaric therapy, a therapeutic method that today arouses admiration and recognition throughout the world. From the first humble experiments involving primitive oxygen-filled chambers to the sophisticated modern hyperbaric chambers, hyperbaric therapy has come a long way, marked by innovation and remarkable discoveries.

This article will show you how what started as a scientific curiosity centuries ago has turned into an essential therapeutic solution capable of healing, renewing and saving lives.

The beginning of hyperbaric therapy

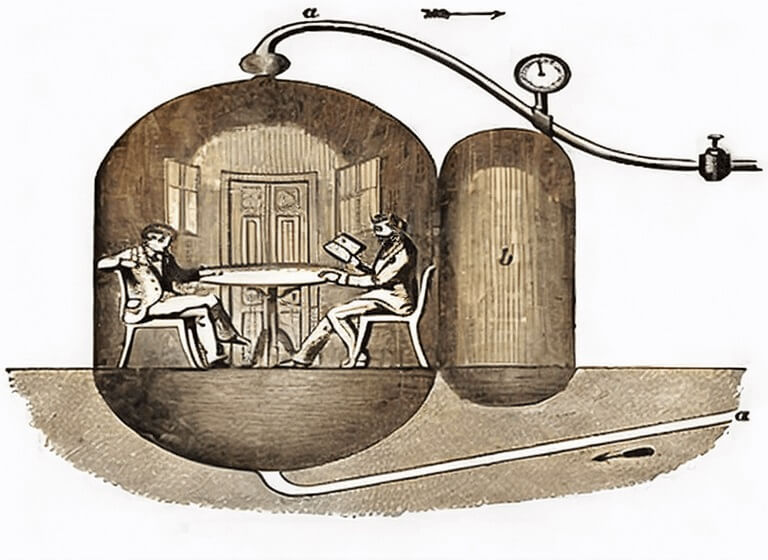

The first documented use of hyperbaric therapy was in 1662, when the physicist Henshaw used a system of one-way valves that changed the atmospheric pressure in a hermetically sealed chamber called the "Domicilium". Without scientific reasoning, at the time he concluded that high air pressures would remedy certain acute conditions, while low pressures would produce beneficial results in chronic disorders. With the help of "Domicilium", Henshaw aimed to improve digestion and prevent lung diseases by manipulating the ambient pressure, but without increasing the oxygen concentration.

19th century discoveries

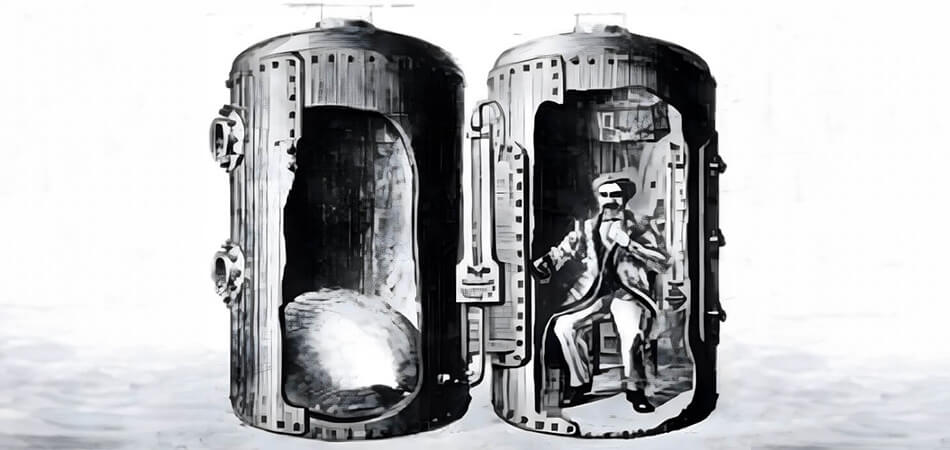

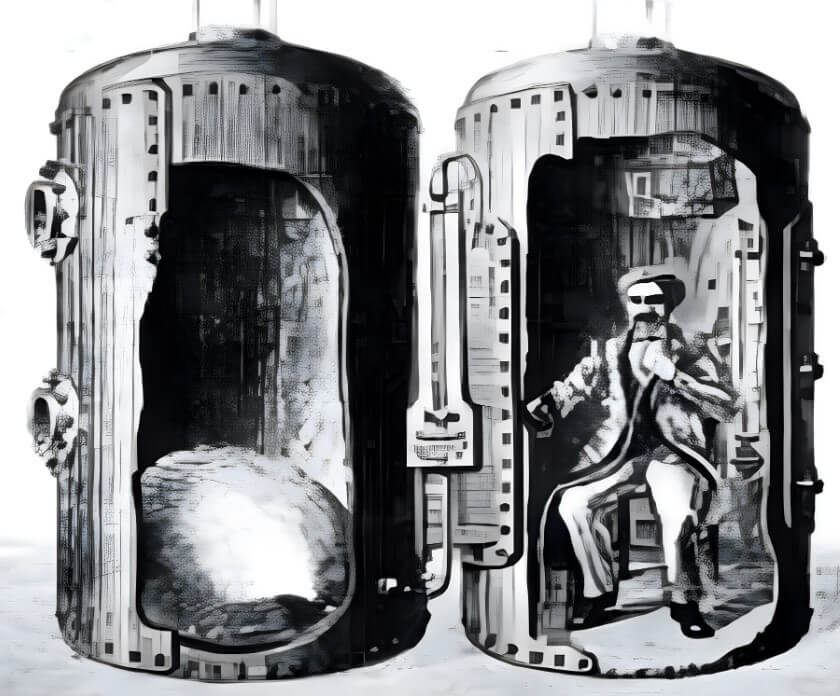

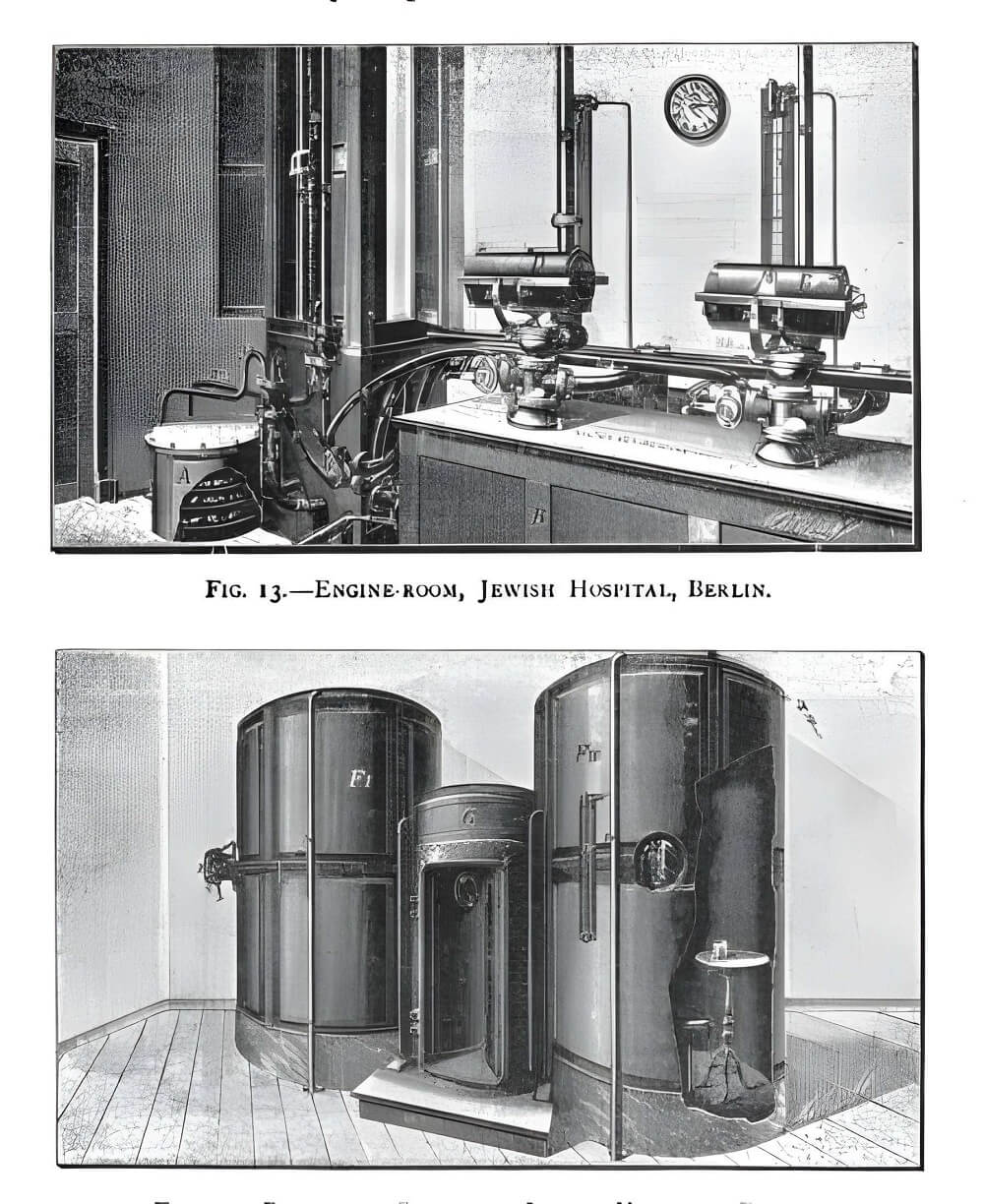

In the early 1830s interest in hyperbaric therapy returned in France. The first to build a hyperbaric chamber was the French physicist Junod. This used inventor Watt's steam engine to go up to 4 atmospheres and was used to treat lung ailments. Junod spoke of his invention as a "compressed air bath" and claimed that it helped to increase the blood circulation of the organs and the brain, thus he believed a better general state of health.

From here on, the rooms became more and more complex. Taberie built a spherical pneumatic chamber with 2 iron pipes, one to provide pressure from the steam made by the hydraulic compressor and another to provide ventilation. He also built an antechamber through which the doctor could enter and exit without disturbing the pressure.

Lange built a cylindrical wrought iron room that could accommodate 4 people. It was equipped with a device for regulating the air flow so that it came in a steady flow, not as a succession of puffs as in previous models.

In the same period, the room built by Leigib consisted of 3 rooms, each of which could accommodate 3 people. An antechamber connected all 3 chambers and was also used as a pressure regulator so that the patient was not affected by sudden pressure increases. Temperature and pressure could be individually controlled.

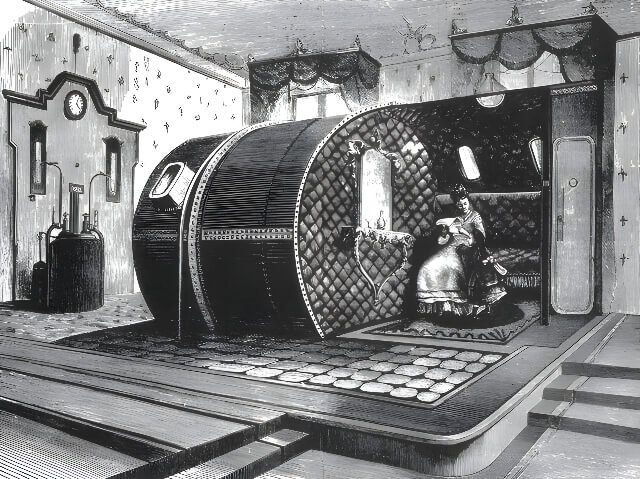

In 1837, Pravaz built the largest hyperbaric chamber that had 12 places and treated lung diseases such as tuberculosis or laryngitis, but also cholera, conjunctivitis or hearing loss.

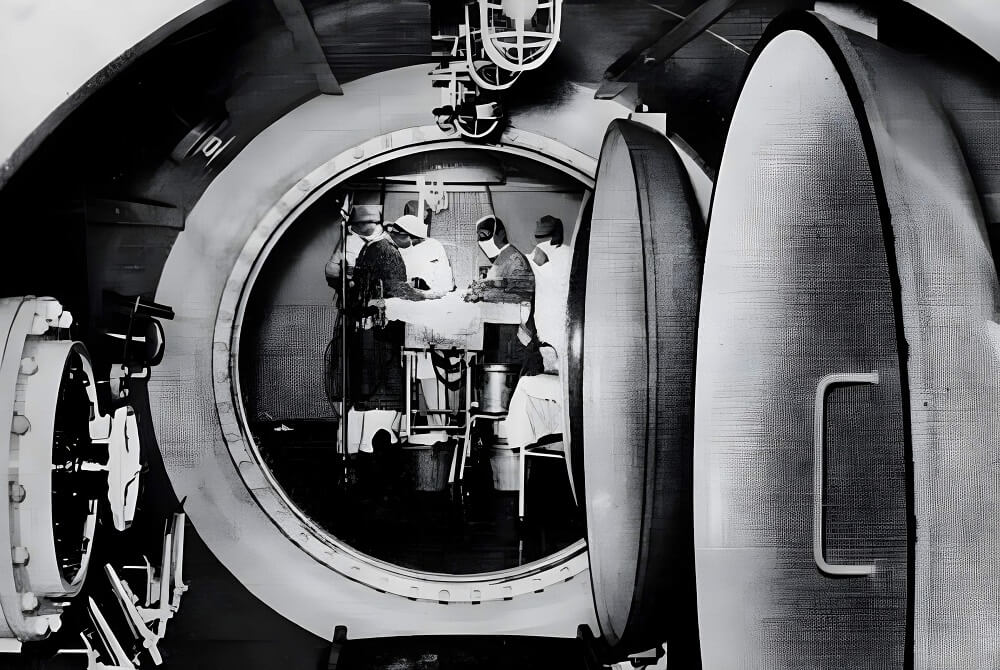

The French surgeon Fontaine created in 1876, the first mobile hyperbaric operating room. The high pressure facilitated the reduction of hernias and relieved the patients' lung problems. Within 3 months, 27 operations were successfully performed in the hyperbaric environment.

Thanks to Paul Bert, French physiologist and politician, also considered the founder of aerospace medicine, more rigorous treatment protocols were created. He studied how the body reacts to high atmospheres and then rapid decompression. He used dogs for this experiment and observed that for a longer duration of decompression, 1-2 hours, the survival rate was 100%.

Hyperbaric chamber in World War I and II

During World War I, Dr. Cunningham built a hyperbaric chamber in 1921 to treat victims of the Spanish flu. He observed remarkable improvements in patients thus treated, especially in those who were cyanotic or comatose. It helped to treat diseases such as syphilis, hypertension, diabetes or cancer.

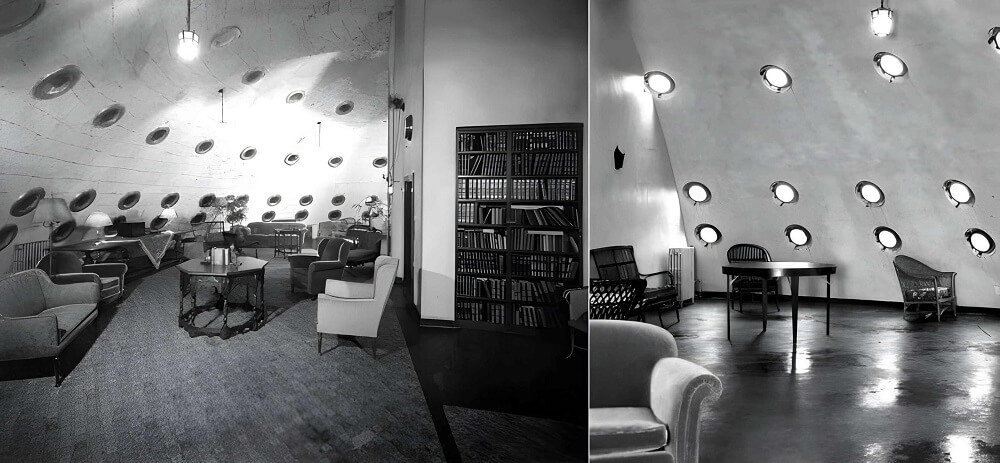

With the financial help of Henry H. Timken, he built the largest hyperbaric chamber in the world. It had 5 floors, 12 rooms on each floor and was equipped like a hotel.

The American Medical Association requested the doctor to validate the claims regarding the effectiveness of hyperbaric therapy, but he did not want to cooperate and so the room was demolished.

The First and Second World Wars hastened advances in hyperbaric medicine, highlighting its need and effectiveness in treating war wounds and other conditions. Treatments in hyperbaric oxygen chambers have reduced mortality and significantly improved wound healing.

The condition that hastened the advance of hyperbaric medicine

Decompression sickness, a condition associated with sudden changes in pressure, perhaps most catalyzed the development of hyperbaric medicine because it paved the way for the recognition of the therapeutic benefits of pressurized oxygen and its associated technology.

The first documented cases of decompression sickness occurred in the early 1840s, when Jacques Triger observed the case of two miners who worked in a caisson under pressure, they developed rheumatic and muscular pains, the condition was to be known later as decompression sickness.

What is decompression sickness?

When swimmers or divers return to the surface, the nitrogen in the blood is released into the body in the form of gas bubbles. The faster the rise, the greater the number of these bubbles. These nitrogen bubbles can cause decompression accidents, which can be serious and cause serious health problems. Symptoms can range from joint and muscle pain to neurological problems or even death in extreme cases.

Hyperbaric therapy, through exposure to higher pressures, reduces the size of gas bubbles and promotes their elimination, relieving symptoms and preventing complications. Over time, hyperbaric medicine has evolved to treat other conditions, from war wounds to burns and carbon monoxide poisoning, providing innovative solutions and improving the quality of life for patients.

As understanding of pressurized oxygen treatment has developed, it has been discovered that hyperbaric chambers can be used not only to treat decompression sickness, but also for other conditions.

Hyperbaric therapy nowadays

After the treatment of President John F Kennedy's baby, public interest in hyperbaric therapy increased considerably.

He was born prematurely and suffered from respiratory distress syndrome. He was immediately transferred to Boston University Children's Hospital for special medical care, where, in an attempt to save his life, doctors tried to treat him using hyperbaric therapy. At that time, hyperbaric therapy was being developed and was being tried for various neonatal conditions, including to improve tissue oxygenation and to treat respiratory disorders.

In 1962, Dr. Smith and Sharp discovered the benefits of therapy for carbon monoxide poisoning. They recommended that people with carboxyhemoglobin above 25% urgently do a 90-minute session at an atmospheric pressure of 3 ATA, and then 2 or 3 more sessions for complete healing. Thus, hyperbaric chambers began to be installed in major university centers in the United States.

This increased number of rooms in university centers has led to studies demonstrating its utility in other conditions as well. Efficacy has been demonstrated in osteomyelitis, stroke patients, multiple sclerosis, hearing loss, myocardial infarction and several diseases of the central nervous system. To date, the FDA and UHMS have approved the use of the therapy in dozens of conditions, and the list is growing with new research

Conclusion

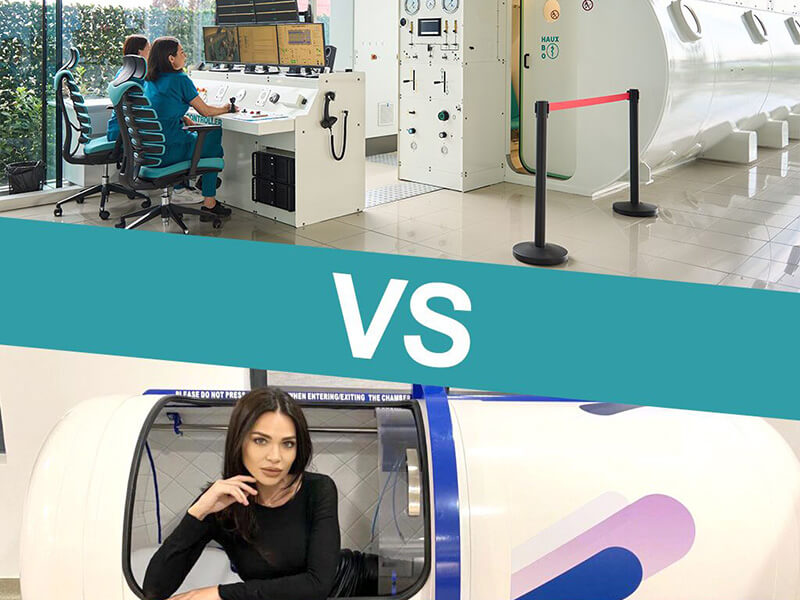

As interest in the benefits of the therapy grew, so did the production of hyperbaric chambers. If at first they were rudimentary, now they are designed to be cost-effective, not take up much space and above all to be extremely safe for patients.

The applications of hyperbaric therapy have expanded in the treatment of conditions such as chronic wounds, burns, tissue necrosis, poisoning, diving accidents and other medical conditions.

Currently, hyperbaric therapy is used in a wide range of medical specialties, including the treatment of soft tissue diseases, neurological conditions, complications of diabetes and other health problems. Also, hyperbaric therapy has become an important option in sports medicine, being used to recover athletes from injuries and to improve performance.

Being a non-invasive and painless treatment, hyperbaric therapy is gaining more and more recognition for its beneficial effects. Whether we are talking about cerebral or neural diseases with a low recovery prognosis or in recovery after physical training, therapy is an adjunct in medicine, with spectacular results.