Article reviewed by: Dr. Sturz Ciprian, Dr. Tîlvescu Cătălin and Dr. Alina Vasile

Article updated on: 22-05-2025

Multiple Sclerosis – causes, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment

- Types and clinical forms of multiple sclerosis

- Causes and risk factors in multiple sclerosis

- How multiple sclerosis is triggered

- Symptoms of multiple sclerosis

- Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis

- Treatment of multiple sclerosis

- Adjuvant therapy and symptom rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis

- Benefits of hyperbaric therapy for patients with multiple sclerosis

- Impact on patient's life

- Perspectives for patients with multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune neurological disease, in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the protective sheath of nerves in the brain and spinal cord. This leads to disruption of communication between the brain and the rest of the body, causing varied symptoms such as vision problems, muscle weakness, and coordination difficulties.

Approximately 2.8 million people worldwide live with multiple sclerosis, particularly affecting young adults between 20 and 40 years old, and more often women than men. In Romania, according to data from recent years, there are about 8,000–9,000 patients diagnosed with MS (approximately 1 in 2,500 people). Although there is no treatment that completely cures the disease yet, there are effective therapies that slow its progression and significantly improve patients' quality of life.

In recent decades, intensive research has led to remarkable progress: today, with early and adequate treatment, many patients with multiple sclerosis can lead an active and almost normal life, with a life expectancy only slightly reduced compared to the general population.

Types and clinical forms of multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) manifests in four main clinical forms, defined by the course of the disease and symptom progression. These are recognized by international guidelines, including the International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in Multiple Sclerosis and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society of the USA.

1. Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS)

This is an incipient form of multiple sclerosis, which involves a first episode of neurological symptoms, such as blurred vision, dizziness, tingling, or muscle weakness, lasting at least 24 hours. Not all patients with CIS develop multiple sclerosis, but some may, especially if MRI investigation shows lesions in the brain or spinal cord.

According to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the risk of developing MS is approximately 60–80% if lesions appear on MRI, but drops to approximately 20% if the MRI is normal.

2. Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (RRMS)

This is the most common form of multiple sclerosis and affects approximately 85% of people initially diagnosed. The disease evolves through episodes (called relapses) in which symptoms worsen or new ones appear. These relapses are followed by periods of remission, in which the patient's condition improves significantly or even completely.

Without treatment, 50% of patients progress to secondary progressive MS (SPMS) in 10-15 years. With modern therapies (e.g., interferon-beta, natalizumab), the conversion rate drops to 20-30%.

3. Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis (SPMS)

This form usually appears in patients who have had the relapsing-remitting form for several years. In SPMS, symptoms begin to worsen gradually, even in the absence of relapses. Walking may become more difficult, fatigue more intense, and some cognitive problems may appear or become accentuated.

Until the advent of modern treatments, approximately half of patients with untreated RRMS reached this form in 10 years. Today, thanks to disease-modifying drugs, this transition can be significantly delayed or even prevented.

4. Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis (PPMS)

It affects approximately 10–15% of patients with multiple sclerosis and manifests through constant worsening of symptoms from the onset, without clear episodes of relapse and remission. For example, the patient may notice that it becomes increasingly difficult to walk or maintain balance.

This form usually appears after the age of 40 and affects men and women equally. The good news is that, starting in 2017, there are approved treatments, such as ocrelizumab, that can slow the disease's evolution.

5. Benign Multiple Sclerosis – does it really exist?

The term "benign MS" is sometimes used to describe patients who, after many years, have very few symptoms and minimal disability. However, doctors warn that even in these cases there may be brain changes that are not immediately felt, but which may advance silently. Therefore, even if symptoms are mild, it is important to go to regular check-ups and have imaging investigations.

Recognition of the MS type is crucial for prognosis and therapeutic strategies. RRMS responds best to immunomodulatory therapies, while PPMS and SPMS require aggressive approaches such as ocrelizumab or stem cell transplantation.

Causes and risk factors in multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic and autoimmune disease of the central nervous system, in which the immune system attacks myelin — the sheath that protects nerve fibers. This process leads to the appearance of lesions that affect the transmission of nerve impulses. The exact cause is not known, but scientists agree that MS arises from a complex interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Here are the most important factors known so far:

1. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection

EBV is a very widespread virus, responsible for infectious mononucleosis. A study published by Harvard demonstrated that the risk of developing MS is 32 times higher in people who have had EBV infection. Moreover, researchers have identified the mechanism by which antibodies against the virus mistakenly recognize a brain protein called GlialCAM, thus causing an autoimmune reaction, a process called molecular mimicry.

2. Genetic predisposition

Although MS is not a hereditary disease in the strict sense, there is an important genetic component. Over 200 genetic variations have been associated with increased risk, the best known being HLA-DRB1*15:01. According to a study, these genes particularly influence immune system functioning. People who have a first-degree relative with MS have a 2–5% risk, and in the case of identical twins, the risk reaches 20–30%. However, these genes do not cause the disease alone; environmental triggering factors are also necessary.

3. Vitamin D deficiency

Vitamin D is essential for proper immune system functioning. People living in areas with little sun, such as northern regions, have a higher risk of developing MS. A meta-study published in 2024 in PubMed showed that low vitamin D levels increase risk by 54%. Vitamin D supplementation and moderate sun exposure are recommended strategies for reducing risk, especially in families with a history of multiple sclerosis.

4. Smoking

Smoking is an important risk factor, influencing both the onset of the disease and its evolution. Studies show that smokers develop more aggressive forms of multiple sclerosis, and disability progression is faster, with an average of 3.7 years earlier than in non-smokers, according to a study published in 2020. Quitting smoking can significantly reduce this risk and even slow disease progression.

5. Obesity in adolescence

Another risk factor is early obesity. It affects immune balance and reduces vitamin D bioavailability, which is stored in adipose tissue. A study published in PMC (2019) shows that obese adolescents have double the risk of developing MS compared to those with normal weight. Therefore, maintaining a healthy body weight from childhood is important.

6. Other investigated factors

- Biological sex: Women are affected by multiple sclerosis 2–3 times more frequently than men, especially in relapsing-remitting forms. Estrogen hormones can influence immunity, partially explaining the differences in incidence.

- Occupational exposure to organic solvents: Toxic substances used in certain industries can increase MS risk, according to some European research, but the exact connection remains under study.

- Intestinal microbiome: The role of gut bacteria in immunity regulation is also being investigated. Intestinal flora imbalances can contribute to the appearance of autoimmune diseases.

Multiple sclerosis is a multifactorial disease. We cannot "blame" a single element, but understanding these risk factors helps us take preventive measures where possible (for example, avoiding smoking, maintaining vitamin D within normal limits) and develop new therapeutic strategies (such as a possible anti-EBV vaccine). It is important to remember that many people with known risk factors never develop the disease, while others, without apparent factors, may develop MS – which indicates the complexity of the mechanisms involved.

How multiple sclerosis is triggered

In multiple sclerosis (MS), the immune system, which normally defends the body against infections, mistakenly attacks components of the central nervous system (CNS) itself. The main target of this autoimmune attack is myelin, the fatty substance that surrounds and insulates nerve fibers (axons), facilitating rapid transmission of electrical impulses along nerves. Myelin deterioration disrupts communication between the brain and the rest of the body, leading to various neurological symptoms.

The basic process in MS is inflammatory demyelination: immune cells, especially autoreactive T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes that produce antibodies, penetrate the CNS and attack the myelin sheaths of neurons. This causes inflammation and myelin destruction, leaving behind areas of scar tissue, hence the name multiple sclerosis. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), these demyelination areas appear as lesions or "plaques." Lesion localization can be varied, but they frequently appear around the cerebral ventricles, optic nerves, brainstem, and cervical spinal cord.

Besides myelin destruction, in multiple sclerosis the axon itself can also be affected. In the early stages, demyelination can be partially reversible: oligodendrocytes can repair some sheaths, and inflammation subsides, allowing function recovery. However, repeated inflammations can lead to irreversible axonal loss. Over time, especially in progressive forms, a chronic neurodegeneration component accumulates: demyelinated nerve fibers become dysfunctional and atrophy, and the brain may suffer volume reduction (cerebral atrophy).

From an immunological perspective, MS is considered an immune-mediated disease, most likely autoimmune. Although the precise antigen of the autoimmune attack has not been identified with certainty, it is suspected that certain proteins in myelin are "confused" by the immune system with a foreign agent. One possible scenario is the molecular mimicry phenomenon, for example, a viral infection (such as EBV) triggers an immune response, and some viral components resemble myelin proteins, leading to a cross-reactive autoimmune reaction.

An interesting aspect recently discovered in MS lesions is the presence of a "virtual hypoxia" environment, practically, although blood circulation is normal, intense inflammation creates locally a state of oxygen deficiency in tissue, which additionally affects oligodendrocytes and neurons. This observation has led to hypotheses regarding the use of hyperbaric oxygenation and to studies on animal models, where oxygen supplementation has shown reduction of demyelinating lesions.

In short, in multiple sclerosis there is a vicious circle of autoimmune inflammation and neuronal degeneration. The inflammatory phase is predominant in the first years, especially in relapsing-remitting forms. The neurodegenerative phase becomes more pronounced in late stages and in progressive forms, being responsible for disability worsening. Current disease-modifying therapies largely target inflammation, trying to reduce the frequency and intensity of autoimmune attacks. A major objective of future research is finding methods to stimulate remyelination and protect neurons to counteract the neurodegenerative component as well.

Symptoms of multiple sclerosis

The clinical manifestations of multiple sclerosis are extremely varied, as the disease can affect any region of the brain or spinal cord. Symptoms can appear suddenly during relapses and may improve partially or completely during remission periods, but sometimes they evolve progressively. Each person with MS can present a unique symptom profile, but there are some frequent manifestations, supported by recent medical studies.

Chronic fatigue (fatigability)

Severe fatigue represents one of the most common and disabling symptoms of multiple sclerosis, affecting most patients at some point. It is described as physical and mental exhaustion disproportionate to the effort expended, with significant impact on daily activities and quality of life. Fatigability has multifactorial causes, including central inflammation, sleep disorders, depression, and adverse treatment effects. Studies show that over 65% of people with multiple sclerosis face fatigue, and for 15-40% this is the most disabling symptom. Factors associated with fatigue worsening are progressive MS subtypes, depression, chronic pain, and comorbidities such as sleep disorders or migraines. Management includes identifying and treating associated causes, adapting daily activities, and sometimes medication treatment.

Vision disorders

Visual problems are frequent, often representing the debut symptom of multiple sclerosis. Optic neuritis, inflammation of the optic nerve, manifests through blurred vision in one eye, decreased color perception (especially red), and ocular pain when moving the eyeball. Usually, these symptoms improve spontaneously, but minor visual acuity deficits may persist. Other manifestations include double vision (diplopia), nystagmus (involuntary eye movements), and difficulties focusing the gaze. A typical sign is Uhthoff's phenomenon, in which visual symptoms temporarily worsen with increased body temperature.

Muscle weakness and walking difficulties

Motor pathway involvement can lead to muscle weakness, most often unilateral or predominant on one side of the body, which influences walking and coordination. Almost half of people with multiple sclerosis may need walking assistance devices after 15 years from onset, but modern therapies can improve this prognosis.

Sensory disorders

Sensory lesions in multiple sclerosis frequently cause paresthesias, numbness, tingling, burning sensation or electric shock, as well as "MS hug" (thoracic tightness sensation). Lhermitte's sign, characterized by an electric current sensation when bending the head, is suggestive of cervical lesions.

Spasticity and muscle rigidity

Motor lesions can determine spasticity – increased muscle tone and involuntary contractions, which can affect mobility and sleep quality. Treatment includes muscle relaxant medications, stretching exercises, and physiotherapy.

Coordination and balance disorders (ataxia)

Cerebellar involvement or its connections can lead to ataxia, intention tremor, and coordination difficulties, increasing fall risk.

Urinary bladder and bowel disorders

Sphincter dysfunctions are frequent: urinary urgency, incontinence, urinary retention, or chronic constipation, often requiring urological management and lifestyle adjustments.

Sexual disorders

Sexual dysfunctions can appear in both men and women, as a result of nerve pathway involvement or the psychological impact of the disease.

Cognitive and emotional disorders

Multiple sclerosis can affect memory, attention, and information processing speed, and depression and anxiety are frequent, having both biological and psychosocial causes. Up to 50% of patients can develop depression throughout their lives.

Besides these major symptoms, each MS relapse can produce a new symptom or another neurological deficit, depending on the area affected at that time. Some symptoms may be temporary, others may persist. Also, over the years, manifestations can change; for example, at onset optic neuritis or numbness often dominate, and after a decade walking and cognitive problems may predominate.

Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis diagnosis can be challenging, especially in early stages, as symptoms can resemble those of other neurological conditions, and the disease does not have a single test that can confirm it with certainty. For this reason, the diagnostic process is based on a combination of clinical, imaging, and laboratory investigations, as well as excluding other possible causes.

Key criteria for diagnosis

The McDonald criteria, last updated in 2017, are the international standard for diagnosing multiple sclerosis. They require demonstrating lesion dissemination in space (in at least two different regions of the central nervous system) and in time (lesions appeared at different times). According to the McDonald Criteria, MS diagnosis confirmation requires two essential conditions:

- Dissemination in space (DIS): identification of lesions in at least two different regions of the central nervous system, such as the brain, optic nerve, and spinal cord.

- Dissemination in time (DIT): lesion appearance at different times, demonstrated either through clinical symptoms or through imaging (active and inactive lesions).

Investigations used in diagnosis

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): This is the main method for identifying demyelinating lesions characteristic of multiple sclerosis. Typical lesions appear in areas such as periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, and spinal cord. Active lesions capture contrast substance (gadolinium), indicating recent inflammation, while old lesions do not capture contrast. Simultaneous presence of both lesion types can demonstrate dissemination in time.

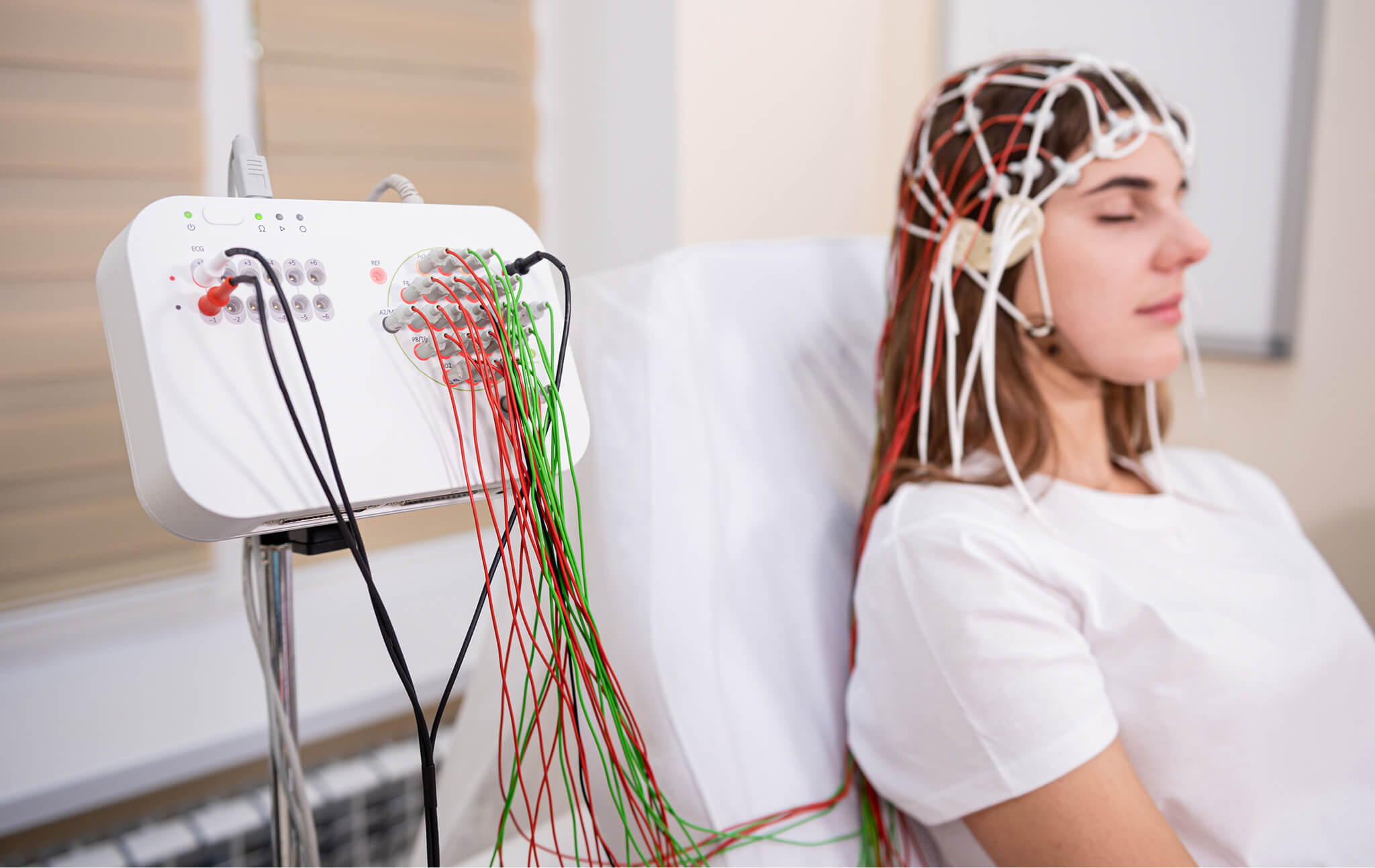

- Evoked potentials (EP): These neurophysiological tests measure the nervous system's response to specific stimuli, evaluating nerve pathway integrity. Visual and somatosensory EPs are frequently used in MS to detect clinically "silent" lesions, contributing to demonstrating dissemination in space.

- Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis: CSF sampling allows identification of oligoclonal IgG bands, present in approximately 80–95% of patients with multiple sclerosis. The presence of these bands, in their absence in blood, suggests a chronic inflammatory process in the central nervous system and can replace the time dissemination requirement according to McDonald criteria.

- Blood tests: Although there is no specific blood test for MS, analyses are essential for excluding other similar conditions, such as lupus, vitamin B12 deficiency, HIV infections, or Lyme disease.

Diagnostic challenges

Multiple sclerosis symptoms can be nonspecific and can mimic other conditions, making diagnosis often delayed. Patients may go through multiple consultations before reaching a neurologist. It is crucial that unexplained neurological symptoms persisting more than a few days be evaluated promptly, to allow early diagnosis and initiation of adequate treatment.

Treatment of multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis treatment has improved significantly in recent decades. Although there is no curative treatment yet, the therapeutic options available today allow effective disease control, relapse reduction, and maintenance of the best possible quality of life. The therapeutic strategy targets three main directions: acute relapse treatment, disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), and symptomatic treatments.

1. Acute relapse treatment

Severe relapses that affect daily functioning are usually treated with intravenous corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone (500–1000 mg/day, for 3–5 days). Corticosteroids reduce inflammation and accelerate recovery, but do not influence long-term disease evolution. Temporary adverse effects may include insomnia, irritability, and blood glucose increases.

In cases where corticosteroids are ineffective or contraindicated, plasmapheresis can be used, a procedure through which autoimmune antibodies are removed from the blood. This is recommended especially in refractory relapse forms.

2. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs)

These treatments are essential in preventing multiple sclerosis progression. These medications reduce relapse rates, prevent new MRI lesions, and delay disability accumulation. They are divided into three categories:

- Injectable DMTs (classic): Beta interferons (Avonex, Rebif, Betaferon) and glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) were the first approved treatments. They reduce relapse rates by approximately 30% and have a well-studied safety profile.

- Oral DMTs: Molecules such as fingolimod (available under the commercial names Gilenya, Fingolimod Zentiva, Fingolimod MSN), teriflunomide (Aubagio), dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), and siponimod (Mayzent) offer superior efficacy and convenient administration. For example, fingolimod reduces relapses by up to 54%, but can cause bradycardia and viral infection reactivation.

- Intravenous DMTs: Infusible medications, such as natalizumab (Tysabri), ocrelizumab (Ocrevus), and alemtuzumab (Lemtrada). These are approved by the European Medicines Agency and are fully reimbursed by the National Health Insurance House.

3. Symptomatic treatment

Even when inflammatory activity is significantly reduced through background treatments, many patients continue to face persistent symptoms, which can profoundly influence quality of life. These residual manifestations require careful and personalized approach to be managed effectively. The most frequent are:

- Spasticity: For reducing muscle rigidity, baclofen (Lioresal 10 mg, Novartis) and tizanidine are used. In severe cases, botulinum toxin injections, such as Vistabel or Alluzience, can be effective.

- Neuropathic pain: Gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline are effective for burning, tingling, and nerve shocks (Cleveland Clinic, 2023).

- Urinary disorders: Anticholinergics and self-catheterization are used depending on dysfunction type.

- Fatigue: Amantadine (Viregyt-K 100 mg), modafinil, and moderate physical exercises help combat fatigability.

- Cognitive disorders: Cognitive training exercises and workplace adaptations can support mental functions.

- Sexual dysfunctions: Can be managed through specific treatments and psychological or couple counseling.

4. Stem cell transplantation (HSCT)

For extremely active forms, refractory to standard treatments, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is an investigated option. The MIST study showed prolonged remissions in severe forms of relapsing-remitting MS. The procedure involves immune system resetting through chemotherapy, followed by reinfusion of own stem cells. It is reserved for specialized centers, given the high risk of complications.

Due to therapeutic advances, the prospects for a young person diagnosed today with multiple sclerosis are much better than 20-30 years ago, with more and more patients managing to have a controlled disease and lead an active life, integrated into society.

Adjuvant therapy and symptom rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis

Adjuvant therapy and rehabilitation represent essential components of multiple sclerosis management, alongside pharmacological treatments. Although they do not directly influence disease activity, these interventions contribute substantially to maintaining functionality, reducing disability, and improving quality of life. The approach is personalized, adapted to each patient's symptoms and disease stage.

Kinesiotherapy and physiotherapy

Adapted physical exercises, performed under the supervision of a kinesiotherapy specialist, reduce spasticity, improve mobility, balance, and contribute to combating fatigue. According to a study published in 2024, regular moderate-intensity resistance and aerobic exercises reduce fatigability and risk of muscle atrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis.

Physiotherapy includes passive mobilizations, stretching exercises, and post-relapse motor reeducation techniques. Additionally, vestibular rehabilitation is recommended for vertigo or balance disorders.

Occupational therapy

Occupational therapy helps patients adapt their daily activities according to remaining capabilities, using energy conservation strategies and assistive devices. According to studies, training on assistive technology use and environmental adaptation have a positive impact on independence of patients with multiple sclerosis.

Psychological counseling and social support

The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is a major psychological challenge. Psychotherapeutic interventions (cognitive-behavioral therapy, group counseling) reduce the risk of depression and anxiety. According to a meta-analysis published in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research (2021), psychological interventions led to significant improvement in emotional state and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis.

Nutrition and supplements

An anti-inflammatory diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, is recommended in international MS guidelines. Vitamin D supplementation is frequently used for its immunomodulatory effect, supported by studies such as that published in Multiple Sclerosis Journal, which shows an inverse association between serum 25(OH)D level and lesion activity on MRI. Additionally, vitamin B12 should be supplemented if deficiencies exist.

Safe complementary therapies

Therapies such as yoga, meditation, pilates, therapeutic massage, or acupuncture can bring benefits in reducing stress and improving general well-being. Although evidence remains limited, a pilot study published in Science Direct (2020) showed a reduction in fatigue and depression after 12 weeks of yoga.

Rehabilitation and adjuvant therapy in multiple sclerosis are essential for an active and dignified life. Through an integrated approach, which includes exercises, psychological support, cognitive and physical adaptations, patients can maintain significant autonomy and high quality of life, even in advanced stages of the disease.

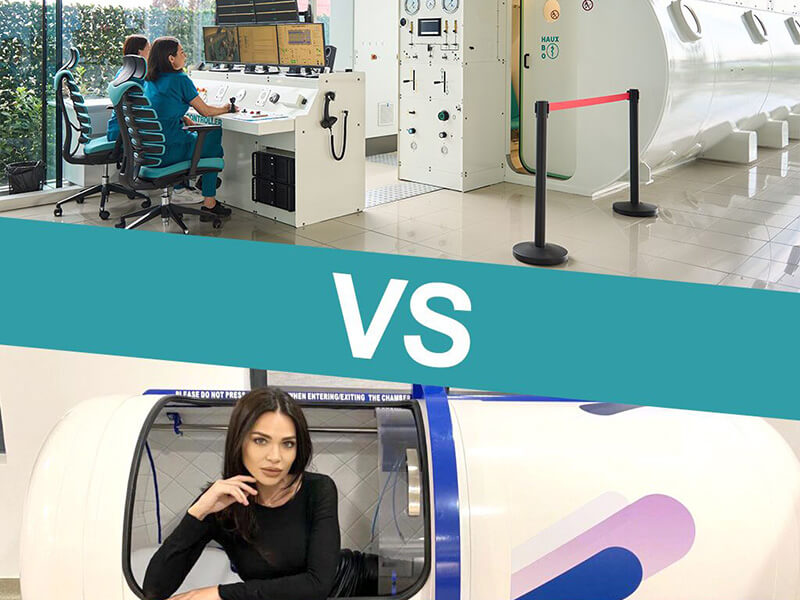

Benefits of hyperbaric therapy for patients with multiple sclerosis

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) is increasingly investigated as an adjuvant option for patients with multiple sclerosis, an inflammatory and neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system. Studies show that hyperbaric oxygen therapy can contribute to significant amelioration of symptoms such as chronic fatigue, motor and cognitive dysfunctions, neuropathic pain, and urinary bladder control problems. By increasing the amount of oxygen dissolved in plasma, hyperbaric therapy provides metabolic support to the brain and spinal cord, areas profoundly affected in multiple sclerosis. Patients often report an improvement in energy levels, decreased spasticity, and better motor coordination after several therapy sessions.

The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in multiple sclerosis

Hyperbaric therapy acts through a series of physiological mechanisms essential in controlling multiple sclerosis progression. First, it has a powerful anti-inflammatory effect, reduces proinflammatory T cell activity and increases secretion of cytokines with protective role. Additionally, hyperbaric oxygen increases partial oxygen pressure in tissues, which determines controlled vasoconstriction with cerebral edema reduction, without compromising neuronal oxygenation.

Another major mechanism is remyelination stimulation: hyperbaric therapy activates oligodendrocytes, cells responsible for myelin layer repair, and supports axonal reparation. Additionally, the therapy improves neuronal metabolism, optimizes mitochondrial function and reduces oxidative stress, contributing to cognitive function recovery and better management of neurological symptoms.

Results from recent clinical studies

The effectiveness of hyperbaric therapy in multiple sclerosis is supported by several international research studies. A randomized double-blind study published in New England Journal of Medicine (1983) showed that 70% of patients treated with hyperbaric oxygen presented significant improvements in mobility and cognitive functions after 20 sessions.

A Japanese study from 1986 reported a 57% decrease in relapses in patients with multiple sclerosis who underwent hyperbaric therapy, compared to the placebo group. In turn, an Italian research from 1990 found that patients who performed weekly hyperbaric therapy sessions for one year recorded a 40% reduction in disability progression.

More recently, a study published in PLoS One (2013) on patients with traumatic brain injuries highlighted that HBOT can induce neuroplasticity and can ameliorate cognitive deficits, with similar mechanisms being relevant for multiple sclerosis as well.

Recommendations and practical indications for patients

The recommended protocol includes between 20 and 40 sessions, with a duration of 90–120 minutes each, at a pressure of 1.5–2.0 ATA. The therapy has the greatest impact if started within the first 5 years from diagnosis, especially in relapsing-remitting forms or mild progressive forms of the disease.

Hyperbaric therapy can be used in parallel with conventional immunomodulatory treatments, offering a synergistic effect in symptom stabilization. However, there are contraindications – such as recent pneumothorax or administration of specific cytostatics, which require careful evaluation before starting treatment.

Although hyperbaric therapy is not a curative treatment for multiple sclerosis, it is a promising therapeutic option, with real potential for symptom amelioration and disease progression slowing. The decision to include hyperbaric therapy in the treatment plan must be made individually, together with a specialist in hyperbaric medicine.

Impact on patient's life

Sclerosis profoundly affects the patient's daily life: physically, emotionally, socially, and professionally. Being a chronic condition, frequently diagnosed between 20 and 40 years of age, MS often interferes with essential life plans, such as career development, starting a family, or maintaining financial independence. The unpredictable nature of the disease, alternation between relapses and remissions, as well as the possibility of progressive evolution induce a feeling of constant uncertainty, with profound psychological effects.

Physical and functional aspects

Multiple sclerosis symptoms vary from chronic fatigue or tingling to severe motor deficits. Some patients may face intermittent limitations: days when they feel energetic and active, alternating with days of exhaustion. In more advanced forms, significant walking difficulties may appear, requiring the use of a cane, walker, or even wheelchair. However, due to modern therapies, more and more patients manage to preserve their mobility and autonomy for extended periods. Invisible symptoms, such as neuropathic pain, vision disorders, or cognitive dysfunctions, can significantly affect the patient's life, although they are not easily observable by those around them.

Professional and financial challenges

Multiple sclerosis affects work capacity, especially in cases of frequent episodes or disability accumulation. Many patients opt for reduced programs or flexible jobs. In Romania, only approximately half of people diagnosed with MS remain professionally active a few years after diagnosis, according to data published by Health Policy Partnership. The European Brain Council report estimated, in 2016, an average annual cost per patient of over €17,100, including productivity losses and medical costs. National programs that offer free treatments through CNAS and social benefits (disability pension, allowances) contribute essentially to reducing financial burden.

Psychological and emotional impact

Multiple sclerosis involves significant emotional adaptation. After diagnosis, many patients experience a wide range of reactions: denial, anger, depression, or anxiety. According to studies, up to 50% of people with MS develop clinical depression. This can have both psychosocial causes (frustration, loss of control) and biological ones (inflammation affects neurotransmitters). Professional psychological support and social support are fundamental for maintaining balanced mental health. Participation in support groups or family involvement in the adaptation process contributes to reducing isolation and emotional stress.

Social relationships and family life

The disease can modify family and couple relationship dynamics. In some cases, the partner takes on additional tasks, and effective communication becomes vital. Sexual dysfunctions, fatigue, or mood disorders can create tensions, but can be overcome through psychological or couple counseling. At a social level, patients may face lack of understanding or stigmatization, especially regarding "invisible" symptoms. Public education is essential for disease demystification: multiple sclerosis does not affect intelligence and does not automatically mean severe disability. Many patients continue to lead active lives, work, travel, and contribute actively in the community.

Realities in Romania

Access to specialized services in Romania remains unequal. Approximately 70% of patients live in rural areas, where access to specialized neurologists and rehabilitation centers is limited. According to MS Barometer 2022, access to rehabilitation in Romania is among the lowest in the EU, and psychological counseling is not reimbursed. The lack of multidisciplinary teams is another problem, leaving the patient to coordinate treatments and adjuvant therapies alone. However, progress is evident: modern treatments have been included in the compensated medication list, and organizations such as the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Romania and APAN actively support patients, offering information, support networks, and logistical support.

Perspectives for patients with multiple sclerosis

The prognosis of patients with multiple sclerosis has improved significantly in the last two decades, due to the advancement of disease-modifying therapies and multidisciplinary care. According to recent data, life expectancy in MS is today only 5–7 years shorter than the general population average, and this gap continues to decrease.

Most deaths recorded among patients with multiple sclerosis are related rather to complications such as infections, pressure sores, respiratory conditions, or cardiovascular comorbidities, and not to direct disease progression. Therefore, prevention of severe disability and careful monitoring of general health status play an essential role in improving longevity and quality of life.

Against the background of modern therapies, an increasing number of patients manage to live actively and independently decades after diagnosis. Studies show that patients who start treatment early and benefit from continuous care have significantly higher chances of avoiding progression to disability. There are multiple documented cases of people with MS who, 20–30 years after diagnosis, continue to work, practice sports, or start families.

The increase in life expectancy is also accompanied by global mobilization. Organizations such as Multiple Sclerosis International Federation (MSIF) and European Multiple Sclerosis Platform (EMSP) support research, public policy development, and increased equitable access to treatments.

At the same time, patient voices are becoming increasingly visible: well-known actors such as Selma Blair or Christina Applegate have spoken publicly about their diagnosis, contributing to stigma reduction and increased social empathy.

Multiple sclerosis is a complex condition, but scientific and therapeutic progress in recent decades has transformed it from a disabling disease into an increasingly well-controllable condition; today, millions of patients worldwide, including Romania, can lead an active life, with adequate medical support, personalized therapies, rehabilitation, and psychosocial support. Although multiple sclerosis remains a challenge with diverse symptoms, unpredictable evolution, and profound impact on quality of life, there are increasingly more resources that support patients: from immunomodulatory treatments and advanced investigations, to psychological counseling, complementary therapies, and support communities. With an integrated, empathetic, and evidence-based approach, patients can become active partners in disease management, and society, from the medical system to family and employers, has the responsibility to create the necessary conditions for them to preserve their autonomy, dignity, and chance for a fulfilled life.