Article reviewed by: Dr. Sturz Ciprian, Dr. Tîlvescu Cătălin and Dr. Alina Vasile

Article updated on: 24-01-2026

Seasonal illnesses: from allergies to viral infections. How do you recover faster?

- What seasonal illnesses actually are

- What are the differences between a cold, a viral infection, and the flu?

- Pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis – when the infection “moves down” the respiratory tract

- Ear infections, sinusitis, allergies – when the nose and ears come into play

- Why some people recover slowly after a viral infection or the flu

- Classic treatment: what remains essential, no matter which modern therapies you choose

- Prevention is the most important factor when it comes to seasonal illnesses

- The role of hyperbaric therapy in recovery after seasonal illnesses

- From the first sneeze to a real recovery plan

Every autumn and winter, the same scenarios repeat themselves in Romania: children miss school, parents go to work with a handkerchief at their nose, and emergency rooms are crowded. We are talking about influenza, respiratory viral infections, pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, ear infections, sinus infections, common colds, and allergies that flare up exactly when life feels busiest and the weather becomes damper.

The less discussed part is that a seasonal illness does not just mean “I felt bad for a few days and that was it.” Many people are left with fatigue, residual cough, breathing difficulties, weakened immunity, and a predisposition to new episodes. This is where smart recovery strategies come into play, not just one pill a day and an evening tea.

At Hyperbarium, the solution to these problems is clear: treatment does not stop when your fever goes down. The goal is to fully restore lung function, calm the remaining inflammation in the body, support immunity, and reduce the risk of complications, using modern technologies such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy, intravenous vitamin therapy, and other complementary therapies, integrated into a serious medical protocol.

Here is what you need to know about seasonal illnesses in Romania and how they are treated to avoid long-term side effects.

What seasonal illnesses actually are

At the European level, it is estimated that up to 50 million people contract seasonal influenza each year, and tens of thousands die annually due to complications, especially the elderly and people with chronic diseases. In recent years, these waves of respiratory infections (including influenza, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2) have been closely monitored across the EU by ECDC, precisely because they place heavy pressure on healthcare systems.

In Romania, as well as in Central and Eastern Europe, every cold season doctors face similar conditions: influenza, viral respiratory infections, pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis (especially in infants and young children), ear infections, sinusitis, common colds, plus allergies that worsen or overlap with viral infections—conditions familiar to every Romanian, especially those with children.

If we look at official data, this is by no means a minor phenomenon. According to the National Institute of Public Health (INSP), during the 2023–2024 flu season, 65,135 clinical cases compatible with influenza (ILI-type infections) were reported in Romania, 12.6% more than in the previous season. Each season there are several hundred to several thousand severe cases requiring hospitalization and sometimes intensive care. For example, in the 2019–2020 season, 365 SARI cases were reported in public hospitals alone, which by extrapolation means approximately 1,900 severe cases nationwide in just one flu season.

The National Institute of Statistics (INSSE) completes this picture through publications on population health, in which respiratory diseases consistently appear among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality, especially in the elderly and patients with comorbidities. Thus, INSSE notes that in the same season, 2,246 laboratory-confirmed influenza cases were recorded, meaning clearly documented cases, not just clinical suspicions.

Consequently, seasonal illnesses are not just a mild episode of discomfort. For many people, they mean prolonged fatigue, persistent cough, labored breathing, worsening of chronic diseases, and a real risk of complications.

So when we talk about the viral season in Romania, we are not referring only to a few isolated colds, but to tens of thousands of cases reported weekly at the peak of the season and hundreds of thousands of episodes throughout the entire season.

What are the differences between a cold, a viral infection, and the flu?

As soon as fever and mucus secretions appear, we say we have the flu. In reality, most of the time we are dealing either with the classic cold or with respiratory viral infections, which are far more common than influenza. Differentiating between them is very important, because treatment differs, as does recovery time for each condition. Therefore, here is what you need to know.

The classic cold is, in fact, a mild respiratory viral infection. It is caused by various viruses: rhinoviruses, seasonal coronaviruses, adenoviruses, and others, and manifests through a stuffy or runny nose, sore or irritated throat, mild chest discomfort, possibly some cough, sometimes low-grade fever or none at all. You feel a bit tired and lethargic, but you do not necessarily need to stay in bed. Usually, the acute episode passes in five to seven days, but the cough can linger, especially in smokers or those with chronic bronchitis.

When we say respiratory viral infection, we are using an umbrella term. This category includes everything from a simple cold to more serious episodes with higher fever, chills, muscle aches, headaches, and marked inflammation of the respiratory tract. In young children, things are even more delicate, because viruses such as RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) can lead to bronchiolitis—that wheezing cough with visible breathing effort that understandably frightens parents. Often, such a viral infection “sets the stage” for bacterial complications: ear infections, sinusitis, or even pneumonia.

The flu is also a respiratory viral infection, but it is treated separately. It is caused by influenza viruses A or B, including the so-called super-flu A(H3N2), and epidemiologically it is entirely different from a simple cold. Onset is usually abrupt: on the first day you feel slightly unwell, on the second day you develop high fever, chills, severe muscle pain, headaches, and a general state of lethargy that makes it hard to get out of bed.

The World Health Organization estimates that globally there are approximately 1 billion cases of seasonal influenza each year, of which several million are severe forms, with hundreds of thousands of deaths. The virus is more aggressive and tends to decompensate pre-existing conditions: cardiac, respiratory, metabolic.

For you as a patient, the difference is not just a label, but matters for two reasons. On the treatment side, influenza is treated with specific antivirals in people at risk, and severe cases are monitored differently than a simple viral infection. On the recovery side, after a mild viral infection you may only need a few days of extra sleep, hydration, and gradual recovery. After a serious flu or pneumonia, however, the body is left with damage: the lungs no longer function as efficiently, general inflammation subsides slowly, and fatigue can last weeks or months.

This is where the idea of smart recovery comes in, not the approach specific to the Balkan space, where once you feel a bit better you immediately resume old habits. For some patients, especially those with chronic diseases or who have had severe episodes, it is essential to discuss with a doctor a plan that does not stop at the classic prescription: hyperbaric therapy for respiratory viral infection or flu to improve oxygenation and reduce inflammation, plus other supportive therapies tailored to each case. The difference between “I had a viral infection” and “I had a serious flu or pneumonia” is seen in practice exactly here: in how quickly and how completely you can resume normal activities after the acute phase has passed.

Pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis – when the infection “moves down” the respiratory tract

If the infection is limited to the nose, sinuses, and throat, we generally speak of upper respiratory tract infections. When inflammation descends toward the bronchi and lungs, things become more sensitive and the risk of complications increases noticeably, especially in young children, the elderly, and people with chronic diseases.

Acute bronchitis means inflammation of the bronchi and almost always occurs after a viral infection. Cough is the main symptom; it may be productive with sputum or dry and extremely irritating. Even after the fever has resolved, the cough can persist for weeks. Clinically, it is known that the infection itself lasts about 7–10 days, but post-bronchitis cough can persist for 3–6 weeks, especially in smokers or those with chronic bronchitis. In children, acute bronchitis accounts for about one fifth of all acute respiratory infections, so it is not an exception but rather a classic cold-season condition.

Bronchiolitis is a condition specific to infants and very young children, in which the bronchioles—the small airways—are affected. It is usually viral, most often caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), responsible in various studies for 50–90% of bronchiolitis cases in children under 2 years of age. It manifests with labored breathing, wheezing, troublesome cough, feeding difficulties, sometimes fever, and agitation or lethargy. In the cold season, true “waves” of bronchiolitis occur: most cases are mild and treated at home, but about 2–3% of children require hospitalization, especially infants under 6 months or those born prematurely, or with heart or lung disease. At this age, however, any respiratory problem is a serious reason to seek medical care or go to the emergency room, because their respiratory reserve is very limited.

Pneumonia refers to inflammation of the lung itself, with involvement of the alveoli, those small “air sacs” where gas exchange takes place. It can be viral, bacterial, or mixed. Typically, the clinical picture includes prolonged fever or fever that reappears after a few days of apparent improvement, productive cough (sometimes with yellowish or greenish sputum), shortness of breath with a sensation of air hunger during minimal exertion, chest pain with breathing or coughing, and a markedly altered general condition, with weakness, loss of appetite, and sometimes confusion in the elderly.

Globally, pneumonia remains one of the leading causes of death in children under 5 years of age, responsible for approximately 15% of deaths in this age group. For Romania, estimates cited by specialists show that 7,000–8,000 people die annually due to pneumonia, meaning about 20–25 Romanians every day, and among young children it is said that approximately one in four deaths is related to pneumonia, placing the country among those with a high burden of this disease.

In severe pneumonia and other acute or chronic lung injuries, standard treatment is based on antibiotics when there is proven or probable bacterial infection, antivirals in certain viral forms, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, hydration, fever control, and respiratory support—from a simple oxygen mask to non-invasive ventilation or even intubation in critical cases. In certain situations—complicated infections, hypoxemia that improves slowly, post-viral or post-pneumonic pulmonary sequelae—hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be used as an adjuvant treatment, dramatically increasing the amount of oxygen dissolved in plasma, improving oxygenation of affected tissues, and supporting infection control and the healing process through its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects.

Ear infections, sinusitis, allergies – when the nose and ears come into play

Acute otitis media (especially in children) often occurs after a respiratory viral infection. The Eustachian tube closes, fluid accumulates behind the eardrum, bacteria find a perfect environment, and painful inflammation develops in the ear. This is not rare at all: globally, an estimated ~709 million episodes of acute otitis media occur each year, and more than half of them are in children under 5. In Europe, up to 50–85% of children have at least one episode of otitis by age 3, and in Romania some pediatric data show that about 90% of children under 6 experience at least one ear infection, and almost half of those under 3 have three or more episodes by that age. Practically speaking, for a parent, ear pain after a cold is almost a childhood “initiation ritual,” not an exception.

Sinusitis means inflammation of the sinuses, those air-filled cavities in the facial bones. When their drainage gets blocked, persistent nasal congestion appears, pressure in the forehead or cheeks, thick nasal discharge (sometimes with an unpleasant smell), headache, and a feeling of facial heaviness and pressure. At first, sinusitis is usually viral, as a continuation of a simple viral infection, but it can become a bacterial complication if secretions stagnate. Beyond symptoms, sinusitis is very common: acute rhinosinusitis has an annual prevalence estimated between 6% and 15% in the population, while chronic rhinosinusitis (symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks) affects about 1 in 10 adults in Europe. You should also know that smoking significantly increases the risk of chronic rhinosinusitis, as does an uncontrolled allergic background.

Seasonal allergies, especially allergic rhinitis, sometimes accompanied by allergic asthma, have a different mechanism. They are not infections, but exaggerated immune reactions to allergens such as pollen, dust, mites, mold. At the European level, studies show that about 20–25% of adults have allergic rhinitis, and the EAACI manifesto draws attention to the fact that over 150 million Europeans suffer from chronic allergic diseases, and it is estimated that up to half of the EU population could have some form of allergy by 2025. In Romania, studies in children and adolescents already show prevalences above 10–15% for allergic rhinitis, with increases in areas with intense pollen exposure, such as regions affected by ragweed.

The important point is that allergies do not come alone: allergic rhinitis is a risk factor both for otitis media with effusion (fluid behind the eardrum) and for chronic rhinosinusitis, precisely because the nasal mucosa is permanently inflamed and drainage works poorly. In the cold season, allergies “intersect” with viral infections: an already inflamed mucosa reacts more aggressively to viruses, symptoms last longer, and the risk of ear infections and sinusitis increases.

When it comes to recovery, things are fairly simple. You can invest in an air purifier so you are less exposed to allergens. Also, a visit to a hyperbaric chamber for allergies can be helpful, because it may reduce inflammation. And through its anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, hyperbaric oxygen therapy can support a more balanced baseline in patients with chronic mucosal inflammation, recurrent respiratory episodes, and comorbidities, when it is recommended by a physician as part of a complex treatment plan—not as an isolated “trick.”

Of course, it must be said that hyperbaric therapy is not a first-line treatment for allergies and does not replace antihistamines, nasal sprays, or allergen avoidance.

Why some people recover slowly after a viral infection or the flu

You probably know someone—or you have been in the situation yourself—of noticing that weeks, or even months, after a viral infection, the body has not fully healed. There are clear medical explanations for slow recovery after respiratory infections, from a simple viral illness to influenza or pneumonia.

The respiratory mucosa needs time to regenerate. When you get a viral infection or the flu, viruses do not just mildly inflame your throat, or simply make it red—they affect delicate structures: the respiratory epithelium, the cilia (the tiny “sweeper” hairs that clear secretions), and microcirculation. Studies on influenza infections and SARS-CoV-2 have shown that full regeneration of the respiratory epithelium can take weeks, sometimes even a few months, especially in smokers or in people with chronic inflammation. This explains why cough and the sensation of “tired lungs” can persist long after the fever is gone and routine tests no longer indicate inflammation or infection.

Systemic inflammation does not stop instantly. During a serious respiratory infection, levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, etc.) rise. Even after the virus is cleared, inflammatory markers may remain mildly elevated, translating into a prolonged semi-flu state: fatigue, vague muscle aches, unrefreshing sleep, low exercise tolerance. Studies in patients after influenza or COVID-19 have shown that, in some of them, subclinical inflammation (slightly elevated CRP, cytokines above normal) persists for months and correlates with symptoms of fatigue and weakness reported by patients.

The immune system is, quite literally, tired. When you fight a serious viral infection, the immune system consumes large reserves of amino acids, vitamins (especially C, D, B vitamins), minerals (zinc, magnesium), and antioxidants. Hormonal, nervous, and metabolic resources are also spent. If after the episode you do not give your body decent sleep, healthy nutrition, and—when needed—targeted support (such as intravenous vitamin therapy), it is very likely you will enter a period of vulnerability: you catch colds easily, any effort exhausts you, and you have concentration issues. It is not weakness of character; it is simply physiology.

Pre-existing chronic diseases slow recovery even more. Ischemic heart disease, heart failure, COPD, asthma, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, obesity—all are associated in studies with a higher risk of severe influenza and pneumonia, and with prolonged convalescence. A diabetic with poor glycemic control, for example, has a higher risk of secondary bacterial infections, heals lung inflammation more slowly, and fatigues more quickly. A patient with COPD or asthma may return very slowly to their pre-infection breathing baseline after an infectious flare. Hence the strong guideline recommendations that people with chronic diseases should be prioritized for prevention (vaccination, monitoring) and for recovery programs after respiratory infections.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, we also have the clearest proof of how serious a post-viral syndrome can be. Terms such as “long COVID” or “post-COVID syndrome” have been described in hundreds of studies: persistent fatigue, concentration difficulties (“brain fog”), shortness of breath with minimal exertion, sleep disturbances, palpitations, anxiety—all present months after the initial episode, even in patients who did not have critical illness. Suggested mechanisms: chronic low-grade inflammation, microcirculation dysregulation, autonomic dysfunction, exaggerated immune reactivation. What matters for us here: it is not only about COVID. Many of these mechanisms apply—more mildly—after other respiratory viral infections too, including influenza or severe viral illnesses.

In addition, the course of healing after the acute episode matters enormously. If, as soon as your fever drops, you abruptly go back to work, do not sleep enough, eat chaotically, and push yourself hard in sports to “make up for lost time,” it is like asking an overheated engine that has just been shut off to immediately run again with the accelerator floored. No wonder it stalls.

That is why the concept of smart recovery after respiratory infections—including hyperbaric therapy for respiratory viral infections—is not a fad, but an important piece of the puzzle. Hyperbaric therapy helps improve tissue oxygenation, reduce inflammation, and modulate the immune response, which can make a difference for patients left with mild hypoxemia, residual lung inflammation, or severe fatigue after a viral infection or pneumonia.

In everyday terms, this means not settling for an immediate improvement—such as the fever going down—but allowing yourself, and asking for, a recovery plan: sleep, nutrition, progressive movement, plus supportive therapies such as hyperbaric therapy and intravenous vitamin therapy, when a doctor considers you have an indication for them. Exactly this type of approach can shorten months of fatigue and cough and reduce the risk that the next viral infection knocks you down completely again.

Classic treatment: what remains essential, no matter which modern therapies you choose

Modern medicine offers many recovery options, but they are pointless if prevention and classic treatment are ignored, because they cannot be replaced. Thus, depending on diagnosis and severity, standard treatment for a cold, viral infection, flu, bronchitis, or pneumonia includes a few common-sense medical elements, supported by European and international guidelines.

Adequate hydration and high-quality rest sound trivial, but they are not. Fluids help thin secretions, maintain tissue perfusion, and reduce the risk of hypotension, especially with fever. European guidelines for acute respiratory infections (including those cited by ECDC and WHO) emphasize that for mild and moderate cases, treatment is mainly supportive: fluids, rest, and nutrition adapted to tolerance. Even if you stay at home but keep working, that is not rest. The body needs a few days in which it is not pushed to the metabolic, physical, or psychological limit.

Antipyretics and anti-inflammatories are used as needed. Paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen) remain the base for controlling fever and muscle aches or headaches, used sensibly and at correct doses. NICE guidelines and WHO recommendations for influenza and acute respiratory infections recommend symptomatic treatment with antipyretics for comfort, not to “normalize at all costs” the temperature—fever is, up to a point, part of the immune response.

Nasal decongestants, nasal irrigation, and symptomatic cough treatment should be considered. Saline sprays, nasal rinses, and, when needed, short-term decongestants (maximum 5–7 days) help drainage and reduce the risk of sinusitis and otitis. For rhinosinusitis, nasal irrigation and intranasal corticosteroids (in allergic or chronic forms) are recommended as key treatment pillars. For cough, guidelines insist on an adapted approach: not all coughs should be suppressed with antitussive syrups; sometimes a mucolytic and proper hydration are more useful so secretions can be cleared.

Antibiotics should be taken only when needed, after consulting a doctor. This is one of the biggest problems in everyday practice. Most viral infections, colds, and even many cases of acute bronchitis are viral, not bacterial. Medical guidelines state very clearly: antibiotics are not recommended in uncomplicated viral respiratory infections, because they do not speed healing and they increase the risk of antimicrobial resistance. The reason you may feel better after antibiotics is that many have anti-inflammatory effects. But in reality, anti-inflammatories (the most popular being ibuprofen-type) can produce a similar effect, with fewer long-term downsides. Therefore, it is very important to talk to your family doctor before taking antibiotics to treat a simple cold.

However, antibiotics should be given when there is suspicion or evidence of bacterial infection: bacterial pneumonia, purulent acute otitis media, bacterial sinusitis (severe or prolonged symptoms, or symptoms that “return” after apparent improvement). In Europe, it is estimated that up to 30–50% of antibiotics prescribed for respiratory infections are unnecessary or unjustified, directly fueling the antimicrobial resistance epidemic monitored by ECDC.

If you have comorbidities or chronic diseases, it is a good idea to discuss with your family doctor to create a personalized treatment plan. For example, for influenza, antivirals such as oseltamivir (found in Tamiflu) may be recommended for certain risk categories (elderly, pregnant women, patients with comorbidities, immunosuppressed) and are most effective if started within the first 48 hours of symptom onset.

Close monitoring is necessary in at-risk patients. For the elderly, cardiac patients, those with COPD, asthma, diabetes, or obesity, European guidelines recommend a lower threshold for seeking medical care and, when needed, hospitalization. Monitoring oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry), respiratory rate, blood pressure, and cardiac function can make the difference between a seasonal viral infection and the early stages of respiratory or cardiac failure.

Prevention is the most important factor when it comes to seasonal illnesses

When we talk about flu, viral infections, pneumonia, ear infections, sinusitis, and allergies, the truth is pretty simple: it’s much easier (cheaper, less stressful) to prevent than to treat—and then struggle through recovery. And when it comes to prevention, we’re no longer in the realm of tradition; we’re in the realm of data: there are studies, European reports, and very clear impact analyses.

The first pillar is vaccination. Influenza vaccination and COVID-19 vaccination remain, in Europe, among the most effective interventions to reduce the risk of severe illness, hospitalizations, and deaths in vulnerable people. A 2025 ECDC report, based on models applied in EU/EEA countries for the 2024/2025 season, shows that vaccination programs prevented between 26% and 41% of flu-related hospitalizations among people over 65, and reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations in the same age group by 14–20%, depending on the country and vaccination uptake. In simple terms: without vaccines, hospitals would have had a quarter to almost half more elderly patients with flu, and a significantly higher share of elderly patients with COVID each cold season.

On the other hand, vaccination coverage remains below what experts recommend. The EU Council and ECDC have long set the goal that at least 75% of older adults and people with chronic diseases should be vaccinated against influenza every year. The ECDC report on recommendations and coverage for the 2024/2025 flu season shows that the median coverage in older adults was only about 47–48%, ranging from roughly 5% to 76% depending on the country; in practice, only a few countries (for example Denmark, Ireland, Portugal, Sweden) come close to the 75% target, while most remain well below it.

In terms of messaging, ECDC itself publicly stated in 2025 that: “influenza vaccination coverage remains below 75% among vulnerable groups and healthcare workers, while cases are rising earlier than usual.”

The World Health Organization, in a recent update about the new A(H3N2) sub-clade K flu strain, nicknamed “super flu,” also warns that the 2025–2026 flu season in Europe started 3–4 weeks earlier than usual, and that vaccination—even if it doesn’t completely prevent infections—significantly reduces the risk of severe disease and hospitalization in risk groups.

The second pillar of prevention is behavior and hygiene—and here we’re not talking only about common sense, but about evidence from studies. Handwashing sounds basic, but meta-analyses of randomized studies show that proper hand hygiene significantly reduces the risk of acute respiratory infections in the community. A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2022 shows that each correct handwashing event is associated with an approximately 3% reduction in the daily probability of developing a respiratory infection, and that well-implemented programs clearly reduce infections and absences from schools and workplaces.

Beyond these classic measures, there is also what WHO and ECDC call “respiratory etiquette”: coughing and sneezing into your elbow or a single-use tissue, ventilating rooms frequently, and staying home when you’re sick instead of going to the office or visiting grandparents with fever and cough. In ECDC’s October 2025 communication, the message is very direct: to reduce pressure on hospitals during respiratory virus season, a package of measures is needed: vaccination, hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, and—when appropriate—mask use in crowded settings.

On an individual level, prevention also means something else: controlling chronic diseases (blood pressure, diabetes, COPD, asthma), quitting smoking, getting decent sleep, reasonable nutrition, and regular movement. Studies clearly show that people with uncontrolled diabetes, obesity, or heart disease have a significantly higher risk of complications and death in influenza and pneumonia compared to healthy people of the same age. In other words, the vaccine helps—but the baseline health “terrain” the virus lands on matters just as much.

If we put all of this together, prevention means more than getting vaccinated every year. It means: vaccinating annually if you are in a risk group (or live with someone vulnerable), keeping chronic diseases under control, building the habit of washing your hands and staying home when you’re sick, and using masks and common sense in crowded spaces during peak viral season. All of these reduce the chance that you end up needing hospitalization, oxygen, or advanced therapies.

On this solid foundation—prevention, correct classic treatment, and a reasonably balanced lifestyle—the discussion about hyperbaric oxygen therapy, intravenous vitamin therapy, and the other Hyperbarium services truly makes sense. Modern therapies don’t come to replace vaccines, hygiene, or personal responsibility; they help where, despite all measures, you’ve had a more severe case, you’ve been left with sequelae, or you simply recover slowly.

The role of hyperbaric therapy in recovery after seasonal illnesses

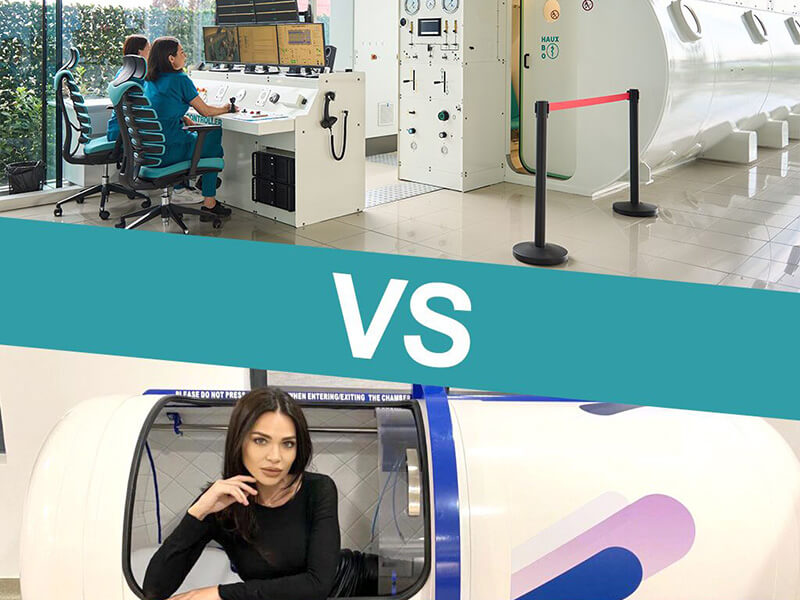

When we talk about hyperbaric oxygen treatment for seasonal illnesses, we mean extra oxygenation of tissues in a pressurized chamber at over 2–3 atmospheres absolute. It sounds complicated, but the idea is simple: at these pressures, oxygen doesn’t just travel bound to hemoglobin—it dissolves massively into plasma and body fluids. This allows oxygen to reach inflamed tissues or areas with poor circulation more effectively, exactly what we see after viral infections, flu, or pneumonias that keep you in bed.

At Hyperbarium, hyperbaric oxygen therapy is performed in a multiplace chamber, a Class IIB medical device manufactured in Germany, with 16 seats, using 100% medical-grade oxygen and pressures up to 3 ATA—i.e., within the range recommended by international ECHM and UHMS guidelines for medical hyperbaric therapy, not “wellness.” Practically speaking, these are hospital-grade conditions, but in an environment dedicated to recovery.

Why choose hyperbaric therapy for seasonal illnesses?

Think about flu, respiratory viral infections, and pneumonias: all of them leave behind inflammation, impaired microcirculation, and sometimes mild to moderate hypoxemia. This is exactly where combinations like hyperbaric therapy and oxygen therapy for respiratory viral infections come in—when the doctor decides the patient can benefit from more effective oxygen delivery than a simple oxygen mask.

The first major effect of hyperbaric therapy is anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory. Multiple studies have shown that hyperbaric therapy can reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines and increase the production of cytokines with anti-inflammatory roles, rebalancing the immune response.

Applied to seasonal illnesses, the mechanism is logical: if after a severe flu or viral pneumonia your lungs remain inflamed and oxygenate less efficiently, hyperbaric oxygen therapy may help reduce pulmonary edema and inflammation, improve oxygenation where the lungs are still not working at 100%, and accelerate tissue repair. That’s why hyperbaric therapy is proposed for seasonal illnesses as a recovery method.

Antibacterial effect and synergy with antibiotics

The second important effect of hyperbaric therapy—especially when we talk about bacterial complications after viral infections (ear infections, sinusitis, bacterial pneumonias)—is its role in fighting microbes.

An experimental study by Almzaiel et al. showed that a single 90-minute HBOT session significantly increases the “respiratory burst” of neutrophils—meaning their capacity to produce oxygen radicals and kill bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus. In other words, in a hyperoxic environment, white blood cells become more efficient at killing bacteria.

A broad review published in 2023 (Zhou et al.) highlights that hyperbaric therapy is generally used as an adjunct treatment in severe or anaerobic infections, precisely because hyperoxia can improve the activity of certain antibiotic classes (beta-lactams, quinolones, aminoglycosides) and can create a hostile environment for bacteria that thrive in low-oxygen conditions.

In plain language: we’re not talking about replacing antibiotics with hyperbaric therapy, but about a partnership—hyperbaric oxygen therapy creates an oxygen-rich environment where white blood cells work more efficiently and certain antibiotics work better. This can matter a lot in hard-to-control respiratory complications, in patients with weakened immunity, or in mixed infections.

Recovery after pneumonia, severe flu, or a complicated viral infection

After pneumonia, severe flu, or an aggressive viral infection, many patients are left with intense fatigue, shortness of breath with minimal effort, the feeling of “tired lungs,” residual cough, and reduced exercise tolerance—exactly that scenario where you feel the illness is over, but your body still can’t keep up.

In such situations, a hyperbaric therapy program integrated into a medical plan (not instead of it) can support the restoration of pulmonary microcirculation, reduce residual inflammation, and accelerate healing. Studies on patients with severe viral pneumonia—especially COVID-19—are encouraging.

A series of case reports and clinical studies (Allam 2022, Kjellberg 2023, Wang 2024) report that hyperbaric oxygen therapy is feasible and safe in patients with severe viral pneumonias, may improve oxygen saturation, reduce inflammation, and even reduce the risk of “treatment failure,” meaning the need to escalate therapy (ventilation, transfer to ICU),

Based on these data and clinical experience, the category of hyperbaric therapy for flu and viral infections may include patients with slow recovery after pneumonia, repeated respiratory viral infections on a chronically fragile baseline, COPD or asthma that decompensates during the cold season, and post-viral sequelae (including post-COVID) with mild hypoxemia or functional impairment. For them, a few hyperbaric oxygen therapy sessions should not be seen as a luxury, but as part of a well-designed protocol, assessed and monitored by physicians specialized in pulmonology and infectious diseases—such as the Hyperbarium team.

Hyperbaric therapy and allergies. What is the role of hyperbaric therapy

Hyperbaric therapy for allergies helps reduce inflammation and support immune regulation. It may attenuate airway inflammation and eosinophilic infiltration—i.e., that exact allergic flare-up in the bronchi—studies suggest.

That said, we are not talking about a first-line therapy for allergies. The foundation remains controlling allergen exposure, allergy-directed treatment (antihistamines, nasal sprays, possibly immunotherapy), and asthma management according to guidelines. But in a context of chronic mucosal inflammation, repeated respiratory episodes, and post-viral fatigue, a visit to a hyperbaric chamber for allergies can play a supportive role: it may contribute to better control of chronic inflammation, improved oxygenation in the setting of bronchial hyperreactivity, and better recovery between overlapping infectious episodes.

What matters is that the decision is not made from Google or ChatGPT, but individually, after an allergy and/or pulmonology consultation. There is no universal protocol for allergies in a hyperbaric chamber—only patients evaluated case by case, where the doctor considers hyperbaric therapy to make sense within a complex treatment plan.

From the first sneeze to a real recovery plan

Seasonal illnesses—from colds and allergies to flu, complicated viral infections, pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, ear infections, and sinusitis—are not just passing episodes. For many people, they leave marks behind: fatigue, cough, reduced resilience, and smoldering inflammation.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy, as practiced at Hyperbarium—in a medical hyperbaric chamber, at therapeutic pressures and with 100% oxygen—is a powerful tool to accelerate healing, modulate inflammation, and support the immune system after respiratory infections. Intravenous vitamin therapy and the other innovative therapies complete this picture, offering an integrated plan tailored to each patient.

If you feel you don’t recover after flu or a viral infection, if you frequently develop pneumonia or bronchitis, if allergies keep sabotaging your cold season, you don’t have to stay stuck in the vicious circle of seasonal illnesses. And the next time viral season hits, you won’t be caught off guard by a cold—you’ll be prepared with a recovery plan. That is, in fact, the difference between passively accepting seasonal illnesses and having a real health strategy.