Article reviewed by: Dr. Sturz Ciprian, Dr. Tîlvescu Cătălin and Dr. Alina Vasile

Article updated on: 06-02-2026

Seasonal flu: types, complications, and treatment with hyperbaric oxygen

- Understanding influenza viruses: Which types of flu are circulating in 2026

- Transmission and contagiousness: why the flu spreads so quickly

- Flu complications: when a common infection becomes dangerous

- Risk groups for complications

- Recovery after flu: why it takes longer than you expect

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy – how it can help you recover faster

- Who hyperbaric therapy is recommended for after flu

- What the actual treatment looks like

- Why you should combine hyperbaric therapy with standard treatments

- Prevention remains the primary strategy

- A modern approach to an old disease

If you have ever had a real case of the flu—not just a simple cold, but that condition where you can barely get out of bed, every muscle aches, and the fever makes you shiver—you know exactly how debilitating this illness can be. Every year at the Hyperbarium Clinic, we see hundreds of patients going through this experience, and the 2025–2026 season has been particularly intense.

That’s why it’s important to talk about the different types of flu, so you know what to expect, about recovery—because the body needs a long time to bounce back after a severe flu—and also about what you can do to speed up recovery through hyperbaric medicine and other complementary therapies.

Understanding influenza viruses: Which types of flu are circulating in 2026

You’ve probably heard on TV about “type A flu” or “type B flu,” but what do these letters actually mean? Let’s clear things up, because the differences matter when it comes to what you can expect.

Type A flu: The main culprit behind epidemics

Type A flu is, unfortunately, the most aggressive and unpredictable form. What makes it so problematic is its unique ability to infect not only humans but also animals: birds, pigs, and marine mammals. This allows it to genetically recombine and emerge with new variants every season, catching our immune system off guard.

The viral structure of type A flu is based on two surface proteins with complicated names: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). You don’t need to memorize these terms, but it’s useful to understand that when you hear about A(H1N1) or A(H3N2), these numbers indicate specific types of these proteins. And yes, which combination is circulating matters, because some are more aggressive than others.

In the current 2025–2026 season, two subtypes are predominantly circulating. A(H1N1)pdm09 is the direct descendant of the virus that caused the 2009 pandemic. Over time, people have developed immunity to it, and it has become a seasonal illness, affecting mainly younger individuals. Adults born before 1957 have some degree of protection due to exposure to older H1N1 viruses.

What you need to know about the A(H3N2) “super flu”

You may have seen dramatic terms in the news such as “super flu” or “pandemic flu wave.” While headlines can be exaggerated, the reality is that the currently circulating A(H3N2) subclade 3C.K variant is indeed more aggressive than we would like.

According to data published by the World Health Organization for the European region in December 2025, this new A(H3N2) subclade K variant accounts for up to 90% of all confirmed flu cases in the European Region, reflecting an unusually early increase in flu activity compared to previous seasons.

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control issued a risk assessment in November 2025, warning that this A(H3N2) K subclade shows significant genetic divergence from the vaccine strain.

What does this mean for you? First of all, that this season’s vaccine may be less effective than in previous years—not useless, but offering reduced protection. Secondly, symptoms tend to be more intense and recovery more prolonged. It has been observed that many patients with this variant report fever above 39°C lasting 4–5 days and profound fatigue that persists for 3–4 weeks.

In Romania, according to INSP data, during the week of January 5–11, 2026, 172 laboratory-confirmed cases were reported, most of them A(H3N2), with 20 cumulative deaths since the beginning of the season. Of these deaths, 17 occurred in people over 65 years old, clearly showing who is most vulnerable.

Type B flu: A milder variant, but not necessarily less problematic

The influenza B virus infects humans exclusively and is considered genetically more stable than type A flu, evolving at a slower pace. This stability means that vaccines tend to be more effective against type B flu, but it does not eliminate the risk of infection. There are two main genetic lineages of influenza B circulating simultaneously: B/Yamagata and B/Victoria, both named after the locations where they were first identified.

Although type B flu is often perceived as milder, this perception can be misleading. In children and adolescents, type B flu frequently causes intense symptoms comparable to those of type A flu. A study published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases analyzed 3,456 pediatric cases and found that type B flu was associated with a longer duration of fever and a higher incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea compared to type A flu.

In adults, manifestations of type B flu are similar to those of type A flu but tend to be slightly more moderate. However, in people with compromised immunity, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease, type B flu can lead to serious complications, including myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) or worsening of congestive heart failure.

Type C flu: The minor form that rarely requires medical attention

The influenza C virus represents the least aggressive and least studied category. Infections with this virus produce mild respiratory symptoms (nasal congestion, occasional sneezing, minimal cough) that mimic a common cold and often go unnoticed. Most people become infected with type C flu during childhood, developing long-term immunity.

Unlike type A and B flu, which generate seasonal epidemics with clear peaks during the cold months, type C flu circulates constantly throughout the year at low levels. There are no vaccination programs for type C flu because it does not pose a significant public health threat and has never been associated with epidemics or pandemics.

Transmission and contagiousness: why the flu spreads so quickly

The reality is that the influenza virus is exceptionally efficient at spreading, which explains why epidemics are practically inevitable.

Transmission occurs mainly through respiratory droplets—those microscopic particles of mucus and saliva that you expel when you cough, sneeze, or even talk. These droplets can travel up to 2 meters and be directly inhaled by people nearby. But there is also a less obvious route: indirect contact transmission. The virus can survive on solid surfaces such as handrails, door handles, and keyboards for 24–48 hours. You touch the contaminated surface, then touch your nose or eyes—and that’s it.

The most insidious aspect is the contagious period: it begins 24 hours before the first symptoms appear. This means you can transmit the flu before you even realize you are sick. In children and people with compromised immune systems, the contagious period can exceed 10 days.

Epidemiological modeling studies and systematic analyses have calculated that a person infected with seasonal flu transmits the virus, on average, to 1.3–1.5 susceptible individuals in an unimmunized community. It may not seem like much, but it is enough to sustain an epidemic in the absence of preventive measures.

Flu complications: when a common infection becomes dangerous

Although most healthy individuals recover completely from the flu within 7–10 days, approximately 10–15% develop complications that require additional medical attention. These complications can range from secondary bacterial infections to severe damage to vital organs.

Respiratory complications

Post-flu pneumonia is the most feared complication, and it can be caused either directly by the influenza virus (viral pneumonia) or by bacteria that take advantage of a weakened immune system (secondary bacterial pneumonia). Primary viral pneumonia usually occurs 2–3 days after the onset of flu and presents with rapidly worsening dyspnea (difficulty breathing), cyanosis (a bluish discoloration of the lips and extremities), and severe hypoxemia (low oxygen levels in the blood).

Secondary bacterial pneumonia, most often caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, or Haemophilus influenzae, typically develops 5–7 days after flu onset, when the patient seems to be starting to recover. The appearance of a new fever, purulent sputum (yellow-green phlegm), and chest pain with breathing are warning signs.

Acute bronchitis is inflammation of the large airways and presents with a persistent cough, increased mucus production, and a feeling of chest tightness. Although less severe than pneumonia, bronchitis can last 3–4 weeks and significantly affects quality of life.

Exacerbation of chronic lung diseases—asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary fibrosis—is another common complication. A prospective multicenter Canadian study published in CHEST followed 4,755 hospitalized COPD patients between 2011–2015 and found that 38.5% tested positive for influenza virus. These patients with confirmed flu had significantly higher rates of critical illness (17.2% vs 12.1%) and mortality (9.7% vs 7.9%) compared with those without flu. Also, a recent U.S. study shows that older patients with COPD and flu have a 30-day hospitalization rate of 34.6%, compared with only 6.1% for those without flu.

Cardiovascular complications

Many patients are surprised when I tell them the flu can affect the heart. But the connection is strong and well documented scientifically. Acute myocardial infarction (a heart attack) is 6 times more likely to occur in the first 7 days after a flu diagnosis, according to a large study published in the New England Journal of Medicine that analyzed 364,227 patients in Ontario, Canada.

The mechanisms are multiple: acute systemic inflammation destabilizes atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries, platelet aggregation increases (the blood tends to clot more easily), and fever and tachycardia place major metabolic stress on the heart.

Myocarditis and pericarditis—meaning inflammation of the heart muscle and the membrane surrounding the heart—are rarer, but they can affect young and physically active people. Atypical chest pain, palpitations, and reduced exercise tolerance are warning signs.

Neurological complications

Influenza encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) is a rare but devastating complication, with an incidence of about 1 case per 100,000 flu infections. It presents with acute confusion, seizures, altered consciousness, and focal neurological deficits. Neuroimaging studies have shown that the influenza virus can directly invade brain tissue or trigger an autoimmune response that attacks myelin (the protective sheath around nerves).

Guillain-Barré syndrome, a neurological disorder in which the immune system attacks peripheral nerves, has an increased incidence after influenza infections. Typical symptoms begin with weakness and tingling in the legs, which progress upward and may eventually affect the respiratory muscles, requiring mechanical ventilation.

Risk groups for complications

Certain categories of people have a significantly higher risk of developing severe complications:

People over 65 are the most affected by the flu, often due to age-related comorbidities. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 70–85% of deaths associated with seasonal influenza occur in this age group, due to aging of the immune system (immunosenescence) and the presence of associated chronic diseases.

Pregnant women, especially in the second and third trimester, when physiological changes of pregnancy (increased cardiac output, reduced lung capacity) increase vulnerability to severe respiratory complications.

People with chronic diseases, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung conditions, kidney failure, liver disease, and immunosuppression, have a much higher risk of severe progression. A report from Romania’s National Institute of Public Health shows that 87% of patients hospitalized with severe flu in the 2023–2024 season had at least one comorbidity.

Children under 2 have an incompletely developed immune system and small airways, which makes them vulnerable to complications, especially respiratory distress syndrome.

Recovery after flu: why it takes longer than you expect

One of the concerns raised by patients who have been through a flu episode is slow recovery. And doctors explain that this is normal. But there’s also a longer version of the answer that we should explain.

Even after the fever and acute symptoms subside, many people continue to experience persistent fatigue, muscle weakness, difficulty concentrating, and exercise intolerance for 2–4 weeks. This phenomenon, known in the medical literature as post-infectious syndrome or “post-flu asthenia,” affects about 40% of people who have had the flu.

The biological mechanisms that explain prolonged recovery are multiple. First, the systemic inflammation generated by the immune response to the virus does not resolve instantly once the virus is cleared. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (signaling molecules involved in the immune response, such as interleukin-6, interferon-gamma, and tumor necrosis factor alpha) remain elevated for weeks, contributing to the feeling of exhaustion.

Second, the flu causes damage to the respiratory epithelium—the layer of cells lining the airways. Complete regeneration of this layer can take 3–4 weeks, during which the airways remain hypersensitive, explaining the persistent cough and increased tendency toward secondary infections.

Research conducted at the Medical Research Council Common Cold Unit in the UK followed adults after laboratory-confirmed flu episodes and objectively measured cognitive performance. Researchers found that influenza B produced 38% increases in reaction times on vigilance and attention tasks compared with healthy individuals. More importantly, performance deficits persisted up to a week after symptoms resolved, indicating that full recovery requires more time than the fever’s disappearance and viral markers. And a recent study from Taiwan involving more than 300,000 patients showed that the flu increases the risk of developing chronic fatigue syndrome by 51%, highlighting the long-term impact of the infection.

For people experiencing persistent post-flu symptoms, intravenous vitamin therapy can be a valuable complementary option. Recent studies in patients with post-viral fatigue have shown that intravenous administration of vitamin C, B-complex, magnesium, and antioxidants leads to significant reductions in fatigue and improvements in sleep, concentration, and physical function. Unlike oral supplementation, intravenous therapies provide 100% absorption and rapid effects, and are specifically recommended for convalescence after viral infections, with visible results after 2–3 sessions by quickly replenishing depleted nutrient stores.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy – how it can help you recover faster

This brings us to the part I’m most passionate about—and the reason many patients come to the Hyperbarium Clinic. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) does not replace standard medical treatment for the flu—antivirals, hydration, rest—but works as a complementary therapy that enhances the body’s natural healing mechanisms.

Systemic anti-inflammatory effects are among the most important benefits of hyperbaric oxygen. Research published in the Journal of Immunology has shown that hyperbaric therapy significantly reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and increases the expression of anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10. In an experimental model of acute lung inflammation, hyperbaric oxygen treatment at 2.5 ATA for 90 minutes daily reduced neutrophil infiltration in lung tissue by 64% after 5 days.

This anti-inflammatory effect explains why recovery after hyperbaric therapy in a post-flu context is often faster than spontaneous recovery, reducing the duration and intensity of post-infectious asthenia.

Improved lung function is another essential benefit. After the flu—especially in cases involving viral pneumonia or exacerbation of chronic lung disease—localized areas of pulmonary fibrosis, interstitial edema, and persistent inflammation can remain and compromise gas exchange. Hyperbaric therapy improves oxygenation of affected lung tissues, reduces edema through controlled hyperbaric vasoconstriction, and stimulates repair of damaged alveolar epithelium.

Boosting antiviral and antibacterial immunity is an additional crucial mechanism. Hyperbaric oxygen significantly increases the bactericidal capacity of neutrophils and macrophages, the immune system cells responsible for destroying pathogens. Research from the University of Pennsylvania has shown that hyperbaric therapy induces significant changes in cellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are fundamental to its therapeutic mechanisms. This property is especially valuable in preventing secondary bacterial infections that often complicate the course of flu.

Reducing oxidative stress and providing cellular protection may sound paradoxical given that HBOT delivers large amounts of oxygen, but research shows that controlled, intermittent exposure to hyperbaric oxygen activates powerful endogenous antioxidant systems. A phenomenon called “hyperbaric preconditioning” occurs, through which cells strengthen their defenses against oxidative stress.

A Polish study of patients undergoing a protocol of 14 hyperbaric therapy sessions measured oxidative stress markers and found that, although a transient increase in oxidation is seen immediately after sessions, by the end of the protocol glutathione peroxidase levels had increased by 26%, providing durable protection against oxidative stress.

Who hyperbaric therapy is recommended for after flu

For patients who develop persistent hypoxemia (low blood oxygen levels) after the flu, even after the acute phase has resolved. Unlike conventional oxygen therapy via mask or nasal cannula, hyperbaric therapy at 3 ATA can achieve arterial oxygen partial pressure values exceeding 2000 mmHg, ensuring optimal tissue oxygenation even in the presence of severe impairment of pulmonary gas exchange.

In patients with post-flu myocarditis or cardiovascular deterioration, HBOT provides the benefits of hyperbaric oxygen by reducing the metabolic workload on the heart and improving myocardial perfusion. Cardiac imaging studies have shown that hyperbaric therapy increases oxygen delivery to the myocardium by 400%, allowing recovery of areas of reversible ischemia.

In cases of post-flu encephalopathy or persistent cognitive impairment, the application of hyperbaric medicine aims to improve cerebral perfusion and reduce residual cerebral edema. Functional neuroimaging research conducted at Tel Aviv University showed that a protocol of 40 hyperbaric therapy sessions at 2.0 ATA improved regional cerebral blood flow by 16–23% in prefrontal and temporal areas, correlating with significant improvements in memory, attention, and executive function tests.

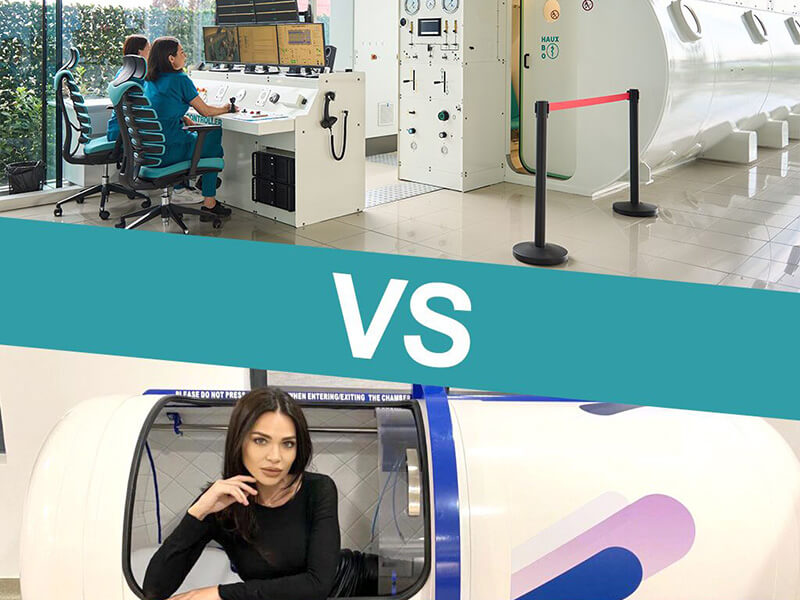

What the actual treatment looks like

The standard protocol for hyperbaric therapy recovery in the context of post-flu complications consists of daily sessions lasting 90–120 minutes at pressures of 2.4–3.0 ATA, depending on case severity and individual response. A complete therapeutic course usually includes 20–30 sessions, administered consecutively or with minimal weekend breaks.

Before starting treatment, you undergo a full medical evaluation: clinical examination, ENT assessment to evaluate Eustachian tube patency (important for pressure equalization in the ears), chest X-ray, and, if you have comorbidities, an electrocardiogram.

During the session, you sit comfortably in the hyperbaric chamber—you can listen to music, watch a movie, or simply relax. The only discomfort reported by most patients is a sensation of pressure in the ears during compression and decompression, similar to what you feel on an airplane, which is easily equalized by swallowing or opening the mouth.

Side effects are generally minor: ear discomfort, transient post-session fatigue, and very rarely, reversible myopia in patients undergoing prolonged protocols of more than 40 sessions.

Why you need to combine hyperbaric therapy with standard treatments

It is essential to understand that hyperbaric therapy does not replace standard medical treatment for the flu, but functions as a complementary intervention that amplifies natural healing mechanisms and accelerates recovery. Medication should also be prescribed by a physician, especially antibiotics. The optimal approach integrates:

Antiviral treatments – neuraminidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir, when administered within the first 48 hours after symptom onset, reduce disease duration by about 1 day and lower the risk of complications by 40–50%.

Supportive therapy – adequate hydration, antipyretics for fever, sufficient rest. It sounds simple, but these measures are fundamental.

Management of complications – antibiotic therapy for secondary bacterial infections, bronchodilators for bronchospasm, all under medical supervision.

Hyperbaric therapy to optimize recovery – especially when spontaneous recovery is prolonged or persistent complications arise.

In severe cases with viral pneumonia, recovery with hyperbaric therapy can be initiated early, in parallel with intensive treatment, to prevent progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome. In patients who have passed the acute phase but experience prolonged recovery with persistent symptoms, oxygen therapy can be applied during the convalescent phase to accelerate return to normal activities.

Prevention remains the primary strategy

Although this article focuses on treatment and recovery, it is important to emphasize that prevention remains the best strategy. Annual influenza vaccination reduces the risk of illness by 40–60%, depending on how well the vaccine composition matches circulating strains. Even when it does not completely prevent infection, it significantly reduces symptom severity and the risk of complications.

Hygiene measures—such as frequent handwashing with soap and water, avoiding touching the face with unclean hands, covering the mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing, and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces—remain essential.

If symptoms appear, early intervention is crucial. Antiviral medications are most effective when administered within the first 48 hours after symptom onset.

A modern approach to an old disease

Seasonal flu remains a significant challenge for global healthcare systems, and the 2025–2026 season, dominated by the A(H3N2) strain, once again highlighted the need for comprehensive therapeutic strategies that go beyond simple symptomatic management. While antiviral treatments and supportive therapy remain foundational pillars, hyperbaric medicine offers a valuable additional dimension by addressing the deeper mechanisms of inflammation, hypoxia, and tissue damage that prolong recovery and generate complications.

Scientific evidence accumulated in recent years shows that hyperbaric oxygen therapy is not an experimental or marginal intervention, but a validated therapeutic modality with well-documented physiological mechanisms and measurable clinical benefits. For patients facing post-flu respiratory complications, persistent asthenia, or prolonged recovery, hyperbaric therapy represents an option worth exploring together with the treating physician.

At the Hyperbarium Clinic in Oradea, the medical team specialized in hyperbaric medicine is prepared to evaluate each case individually and develop personalized therapeutic protocols that optimally integrate this advanced technology into the post-flu recovery pathway. If you are experiencing persistent symptoms after the flu or complications that affect your quality of life, an evaluation consultation can help determine whether hyperbaric therapy is appropriate for your specific situation.

The flu is an old disease, but the medical tools we have to fight it continue to evolve. Combining classical medical wisdom with modern therapeutic innovations gives us the chance to transform a potentially debilitating experience into a temporary episode, with full recovery and no long-term sequelae.