Article reviewed by: Dr. Sturz Ciprian, Dr. Tîlvescu Cătălin and Dr. Alina Vasile

Article updated on: 21-04-2025

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) - What it is, causes, symptoms and treatment

- What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

- Categories and types of PTSD

- Causes of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- What are the symptoms of PTSD?

- PTSD in children and adolescents

- How is PTSD diagnosed?

- What are the treatments for PTSD?

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of PTSD

- Difference between PTSD and other similar disorders

- PTSD in Romania – Challenges and solutions

- PTSD – a global problem and the impact on daily life

Some wounds are not visible, but they hurt just as much. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an invisible scar left by deep traumas, a psychological condition that transforms memories into heavy burdens to bear. It makes no distinction between victims, it can affect soldiers returning from the front, survivors of violence, accidents, or even people who have helplessly witnessed tragedies.

Although PTSD remains an often misunderstood problem, its reality is undeniable: approximately 3.9% of the global population will experience this disorder at some point in life, and in Romania, over 5% of adults are affected. Its impact is not limited to inner suffering; it can destroy relationships, careers, and sometimes even the hope of living a normal life again. But PTSD does not have to be a sentence. With early recognition, support, and appropriate treatment, there are paths to healing. Here's everything you need to know about this disorder.

What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) is a psychiatric disorder that occurs in some people after they have experienced or witnessed traumatic events that have put their life or integrity in danger. According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), PTSD can occur following natural disasters, serious accidents, acts of terrorism, war/combat, rape, or other physical and sexual assaults. Such events are perceived as extremely threatening, and the trauma exceeds the individual's usual capacity and coping mechanisms.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines PTSD as a mental health condition that develops in some people after exposure to traumatic or frightening events (such as, for example: natural disasters, accidents, violent attacks, military actions), events in which the person was injured, threatened with death, or witnessed the injury or death of others. PTSD was previously also called "shell shock" (after World War I) or "battle fatigue" (after World War II). However, not only war veterans can develop PTSD; it can affect anyone, regardless of age, gender, or culture, if exposed to a severe traumatic event.

For diagnosis, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) includes PTSD in the category of trauma and stress-related disorders. DSM-5 establishes that for a PTSD diagnosis, direct or indirect exposure to an actual or threatened traumatic event (death, serious injury, or sexual violence) is necessary, followed by a set of persistent symptoms from multiple categories (re-experiencing, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, increased reactivity), lasting more than one month and causing significant distress or functional impairment.

The World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) similarly defines PTSD, requiring that the event was extremely threatening or terrifying, and that the symptomatology includes intrusive re-experiencing of the trauma, avoidance, and hyper-reactivity, all associated with significant impairment in daily life.

Categories and types of PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is not classified into distinct categories in the same way that other mental disorders are classified. However, there are different types and presentations of post-traumatic stress disorder, which can vary depending on the severity of symptoms, their duration, and triggering factors.

Acute PTSD

Acute PTSD is the most common form and manifests in the first three months after the traumatic event. Symptoms include intense flashbacks, avoidance of trauma-related memories, and a continuous state of psychological and emotional hyperarousal. In many cases, symptoms may diminish in intensity over time, especially if the affected person receives adequate support and psychological treatment. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and gradual exposure to traumatic memories are the most effective intervention methods for this form of PTSD.

Chronic PTSD

If symptoms persist for more than three months, the condition becomes chronic. Chronic PTSD can have a profound impact on social and professional functioning, leading to depression, social isolation, and severe mental health problems. Some neurobiological studies have shown that chronic PTSD is associated with changes in the hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex, brain structures involved in regulating emotions and stress response.

In addition, chronic PTSD increases the risk of comorbidities, such as major depressive disorders, substance abuse, and suicide. People with this form of PTSD may experience deterioration in interpersonal relationships, problems at work, and difficulties in maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Delayed-onset PTSD

Delayed-onset PTSD occurs when symptoms begin six months or later after the traumatic event. This is a form of PTSD frequently encountered in war veterans, survivors of childhood abuse, or people exposed to prolonged trauma, such as domestic violence. One of the triggering factors for this type of PTSD is exposure to additional stress, which can reactivate latent traumas.

Research suggests that delayed-onset PTSD may be more difficult to treat, as the affected person has already developed unhealthy coping mechanisms and may have difficulties identifying the connection between current symptoms and the initial traumatic event.

Complex PTSD (C-PTSD)

Complex PTSD (C-PTSD) is a severe form of PTSD that occurs as a result of prolonged exposure to repetitive trauma. This is frequently encountered among survivors of childhood abuse, domestic violence, or torture.

In addition to the classic symptoms of PTSD, C-PTSD also includes:

- Difficulties in regulating emotions – sudden mood changes, intense episodes of anger or anxiety.

- Problems in forming and maintaining interpersonal relationships – tendency to avoid social connections or repeat dysfunctional relationship patterns.

- A distorted self-image – feelings of chronic guilt, shame, or the sensation of being "wrong" or inferior.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized Complex PTSD as a distinct condition in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11)

Causes of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Severe psychological trauma is the direct cause of PTSD, but not everyone exposed to trauma develops this disorder. In fact, epidemiological studies show that, although ~70% of people experience at least one traumatic event throughout their life, only a minority develop PTSD (about 5-6%).

Genetic factors seem to play a significant role in individual vulnerability: research on twins suggests a moderate heritability of PTSD (between ~30-40%). For example, a recent study on 16,000 twins estimated that genetic predisposition to PTSD is ~35% in women and ~29% in men. Thus, some genes involved in stress regulation, memory, or emotions (such as those for the serotonergic system or the HPA axis) may increase the risk of PTSD in the presence of trauma.

Biological and neuroanatomical factors also contribute to susceptibility to PTSD. In the brain, structures involved in memory and stress response, such as the hippocampus and amygdala, may undergo changes. Many imaging studies have reported reduced hippocampal volume in people with PTSD compared to those without PTSD.

The hippocampus is essential in memory processing, and a chronically high level of stress hormones (such as cortisol and adrenaline) can affect hippocampal function, preventing the proper consolidation of traumatic memories. This explains why trauma memories often remain unintegrated and intrusive in PTSD.

Also, abnormal levels of stress hormones have been observed: adrenaline and noradrenaline. These hormones may remain elevated long after the traumatic event, keeping the body in a continuous state of "alarm". This biological hyperarousal manifests through hypervigilance, insomnia, exaggerated reactivity – typical PTSD symptoms.

Environmental and experiential factors greatly influence the probability of PTSD occurrence. First, the nature and severity of the trauma suffered matter: intentional and violent traumas (e.g., sexual violence, torture, assault, theater of war) are much more likely to lead to PTSD than natural disasters or accidents. For example, the PTSD rate among survivors of sexual assaults or veterans exposed to intense combat is substantially higher than in the general population. The repetition or duration of trauma (cumulative trauma or chronic abuse in childhood) also increases the risk and can lead to more complex forms of PTSD.

Another critical environmental factor is post-trauma social support. People who feel supported by family, friends, or community after the event have a lower risk of developing PTSD. Emotional support and validation of experiences can facilitate natural healing. On the other hand, lack of support or stigmatization (an example would be blaming the victims) amplifies post-traumatic stress.

Other risk factors include a personal history of mental disorders (pre-existing anxiety or depression), previous exposure to trauma, childhood marked by abuse or neglect, as well as personality traits (for example, the tendency toward anxious reactions).

What are the symptoms of PTSD?

PTSD symptoms are divided into four main categories, according to DSM-5 criteria and APA descriptions: intrusive re-experiencing of trauma, avoidance, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and hyperarousal. These symptoms usually appear within the first 3 months after the traumatic event, but sometimes the onset can be delayed by months or even years. Immediate suffering after trauma does not mean PTSD; many people have acute reactions (shock, anxiety, insomnia) that improve within a few weeks. PTSD is diagnosed only if symptoms persist or worsen after less than a month and significantly affect daily functioning.

1. (Intrusive) re-experiencing of the traumatic event

The person mentally relives the trauma in various intrusive and unwanted forms: flashbacks (very vivid memories, as if the event were happening again), nightmares and repetitive dreams about the trauma, invading images or thoughts related to the event. These intrusive memories are accompanied by intense psychological stress and notable physical reactions (accelerated pulse, sweating, trembling) when exposed to cues that remind of the trauma. For example, a survivor of a car accident may have flashbacks to the sound of impact or may "relive" the feeling of horror when hearing the screeching of brakes.

Nightmares in PTSD can be repetitive and terrifying; in children, bad dreams may not faithfully reproduce the trauma, but contain themes of fear and danger. In severe cases, dissociative episodes occur in which the individual loses contact with the present and acts as if the trauma is happening again (e.g., hiding under a table believing it's an earthquake). These re-experiencing phenomena are the core of PTSD and cause profound suffering.

2. Avoidance behaviors

People with PTSD actively try to avoid anything that reminds them of the trauma. This may include avoiding places, people, activities, or situations that trigger memories (for example, avoiding driving after a car accident, avoiding news about assaults, refusing to talk about what happened).

They also avoid thoughts or emotions related to the event, in an attempt to mentally detach, to "bury" the trauma. Unfortunately, this long-term avoidance is counterintuitive: although it reduces anxiety momentarily, in the long run it prevents the processing of trauma and maintains symptoms. Avoidance amplifies social isolation. For instance, someone who avoids anything that reminds them of trauma may end up distancing themselves from family, friends, or giving up everyday activities (work, school).

3. Negative cognitive and emotional symptoms

After trauma, lasting changes in how the person thinks and feels frequently occur. People with PTSD may have difficulty remembering important aspects of the event (dissociative amnesia) or may develop persistent negative perspectives about themselves, the world, and the future. For example, they may believe "I'm not safe anywhere" or "it was my fault that it happened." Overwhelming negative emotions often appear – intense fear, guilt, shame, or anger – without being able to rediscover positive emotions (joy, satisfaction).

Interest in pleasurable activities disappears (anhedonia), and the person becomes detached and alienated from others, having difficulties feeling affection or closeness (even towards loved ones). In PTSD, the emotional world "contracts," meaning emotional numbness or negative emotions predominate, and self-perception can be profoundly affected (some feel "wrong" or hopeless). In children, signs may include regression (lost developmental achievements), repetitive play expressing elements of trauma, or themes of guilt and confusion related to the event.

4. Hyperarousal and increased reactivity symptoms

PTSD keeps the body in a chronic state of alert, as if danger were always present. Patients may be hypervigilant, scanning the environment for possible threats, easily startled by sudden noises or movements (exaggerated startle response). Difficulties in concentration and insomnia can be observed (both falling asleep and maintaining sleep can be problematic due to nighttime anxiety and nightmares).

Also, irritability and disproportionate outbursts of anger are frequent, sometimes with verbal or physical aggression towards others, even in the absence of a real danger. Some become reckless or self-destructive (for example, driving dangerously, consuming substances in excess) – behaviors that can be seen as attempts to reduce internal tension or to regain control in a maladaptive way. These hyperarousal symptoms reflect an inability to regulate the neurobiological stress system: the body remains stuck in "fight or flight" behavior, with a high level of adrenaline, even in safe situations.

PTSD in children and adolescents

Children and adolescents can develop PTSD in response to traumas such as physical or sexual abuse, serious accidents, domestic violence, or the death of a parent. However, manifestations of PTSD in children often differ from those of adults.

How does PTSD manifest in children?

In children younger than six years, PTSD symptoms may include:

- Repetitive play that reflects the trauma – a child who has witnessed a car accident, for example, may repeatedly reenact the scene with toys.

- Developmental regression – loss of previously acquired skills, such as bladder control or the ability to sleep alone.

- Exaggerated fears and separation anxiety – children may become extremely attached to parents or may manifest intense fear in their absence.

In adolescents, PTSD symptoms may more closely resemble those of adults, but may also include:

- Risk behaviors – alcohol consumption, drugs, or risky sexual behavior.

- Social isolation – withdrawal from activities and relationships.

- Difficulties in concentration and decreased school performance – difficulties in maintaining attention and learning.

Risk factors for PTSD in children

Certain variables can influence the likelihood that a child will develop PTSD after a traumatic experience. Among the most important risk factors are:

- Duration and severity of trauma – repeated or prolonged trauma (for example, chronic abuse) increases the risk of PTSD.

- Social support – children who receive support from family and community after the event have better chances of recovery.

- Family history of mental illness – genetic predisposition and family history of anxiety or depression can contribute to the development of PTSD.

Differences between PTSD symptoms in adults and children

In children, PTSD symptoms can manifest differently than in adults. Instead of detailed flashbacks, young children may express trauma through repetitive play, where they recreate elements of the traumatic event. They may also have vague nightmares without clearly remembering their content.

In addition, PTSD in children can be associated with developmental regression, such as returning to earlier behaviors (for example, nocturnal enuresis or excessive fear of separation from parents). Adolescents with PTSD may engage in risk behaviors, such as alcohol or drug use, as well as an accentuated tendency toward social isolation.

However, clinical studies show that children seem to have a somewhat lower risk of developing PTSD compared to adults (especially under 10 years), possibly due to different mechanisms of stress processing in the developing brain.

How is PTSD diagnosed?

PTSD diagnosis is based on a careful clinical evaluation conducted by a mental health professional (psychiatrist, clinical psychologist). Generally, DSM-5 or ICD-10/11 criteria are followed, assessing exposure to trauma and the presence of symptoms from each category (intrusion, avoidance, negative cognitions/mood, hyperreactivity) for over a month. The doctor or psychologist will conduct a structured clinical interview to gather detailed history of the traumatic event and associated symptoms.

The standard for diagnosis is the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) – a structured 30-item interview administered by a trained clinician, which evaluates each PTSD symptom according to DSM-5, both in frequency and intensity. CAPS-5 allows quantification of PTSD severity and verification if criteria are met (for example, at least one intrusion symptom, one avoidance symptom, two negative cognition symptoms, two hyperactivity symptoms, etc., plus duration and impairment). The CAPS-5 score results in a total severity score, but also scores on symptom clusters, providing a detailed profile of the disorder.

An advantage of CAPS is that it can establish not only if the diagnosis is present, but also the degree of severity, and can be repeated to monitor evolution under treatment. Being a complex interview, CAPS-5 requires about 45-60 minutes and clinical expertise.

Besides the clinical interview, self-assessment instruments (questionnaires) are frequently used that can help with screening or monitoring symptoms. The most used instrument is the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), a self-report questionnaire with 20 questions corresponding to the 20 PTSD symptoms defined by DSM-5. The patient evaluates on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) how much each symptom has bothered them in the last month. PCL-5 can be used for: screening (identifying those who might have PTSD), monitoring progress (decrease in score during therapy indicates improvement), and even to support a provisional diagnosis. A total PCL-5 score above a certain threshold (usually 33 or 38, depending on the clinical context) likely suggests PTSD, but the final diagnosis must be confirmed through clinical interview.

Guidelines recommend interpretation of PCL-5 by a clinician, especially since some people may over or under-report symptoms. PCL-5 is, however, very useful in practice – it is short (completed in ~5-10 minutes) and has proven reliable and valid in various studies, correlating well with CAPS-5 scores.

Other instruments used can be Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R), Trauma Symptom Inventory (TSI) or, for children, Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS). Also, associated comorbidities (depression, anxiety, substance abuse) are often evaluated through specific questionnaires, and general health status is investigated (PTSD can coexist with medical problems, e.g., chronic pain).

In diagnosis, it is essential to exclude other causes: it is verified that symptoms are not better explained by another disorder (e.g., flashbacks vs. hallucinations from psychosis) or effects of substance use. Once the PTSD diagnosis is established, the clinician will note type specifiers (for example, if there are dissociative symptoms, it can be specified as "PTSD with dissociative symptoms").

There are no laboratory tests (blood, biological markers) that confirm PTSD; the diagnosis is clinical. However, research continues on biomarkers (stress hormones, neuroimaging, etc.) to better understand this disorder. In practice, combining structured interview (e.g., CAPS-5) with self-assessment scales (e.g., PCL-5) and clinical observation provides the best accuracy. Early diagnosis is important, as it allows early initiation of treatment, improving long-term prognosis.

What are the treatments for PTSD?

Post-traumatic stress disorder can have a profound impact on a person's life, but available treatments can significantly improve quality of life and help manage symptoms. Currently, treatments for PTSD include psychotherapy, medication, and complementary therapies, each having an essential role in the recovery process. Choosing the right method depends on the severity of symptoms, the patient's medical history, and response to previous treatments.

Psychotherapy in PTSD

Psychotherapy is one of the most effective approaches for treating PTSD. Studies show that psychological interventions can significantly reduce symptoms and improve patients' emotional and social functioning.

Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), including variants such as Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) and Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE). These therapies help the patient reprocess traumatic memories in a more adaptive way. For example, prolonged exposure involves repeatedly narrating the trauma in a safe therapeutic context, so that anxiety gradually fades (habituation) and avoidance is reduced. CPT, on the other hand, focuses on identifying and correcting irrational thoughts related to trauma (exaggerated guilt, negative worldview) and transforming them into more balanced perspectives. These therapies have high success rates: many people show significant decrease in symptoms after ~12-16 sessions and even remission of diagnosis.

EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing): A less conventional psychotherapy, but recognized by WHO and APA as effective in PTSD, EMDR combines recalling traumatic images with bilateral stimulation (usually eye movements guided by the therapist or other alternating tactile/auditory stimuli). The goal is to facilitate emotional reprocessing of memories, integrating them adaptively. EMDR has shown in studies efficacy comparable to trauma-focused CBT, also being recommended in WHO guidelines as a first-line therapy.

Stress and anxiety intervention techniques: many therapies include elements of coping skills training, progressive muscle relaxation, mindfulness, etc., to help the patient manage hyperreactivity. Stress Inoculation Training (SIT), for example, teaches practical anxiety reduction skills (controlled breathing, rapid cognitive restructuring) and has proven beneficial in alleviating PTSD symptoms. Therapy is often trauma-focused, because avoiding talking about trauma maintains symptoms.

Medications used in PTSD

SSRI antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRI) constitute the internationally accepted first-line pharmacological treatment. Of these, Sertraline and Paroxetine are officially approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of PTSD and have the most consistent scientific support regarding their effectiveness in reducing core symptoms (flashbacks, avoidance, general anxiety). Other SSRIs, such as Fluoxetine, or SNRIs (serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, SNRI) such as Venlafaxine XR, are also recommended by some guidelines as first-line options, having significant clinical evidence.

These antidepressants help regulate brain chemistry affected by chronic stress – especially serotonin and norepinephrine – which leads to improved mood, decreased hypervigilance, and improved sleep in many patients.

Tetracyclic antidepressants such as Mirtazapine or tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline) have also been studied, sometimes used when SSRIs don't work, but the profile of adverse effects limits their use.

Medication for sleep and nightmares: A very disturbing symptom in PTSD is traumatic nightmares and chronic insomnia. A medication often used to treat nightmares is Prazosin, an adrenergic alpha-blocker. Studies have shown that Prazosin can significantly reduce the frequency and intensity of nightmares and improve sleep quality.

Although the results of recent research are mixed (some newer studies found no differences from placebo in all patients), Prazosin remains a valuable tool, especially for those with pronounced adrenergic hyperactivation (tension, sweating, elevated nocturnal pulse).

Adjuvant medication: In some cases, atypical antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone, olanzapine) are also used as an adjuvant to antidepressants for patients with very severe symptoms or traumatic psychoses. However, evidence for antipsychotics in PTSD is mixed, and they are not routinely recommended, being reserved for situations resistant to other treatments. Beta-blockers (propranolol) have been investigated for preventing PTSD immediately after trauma (administered in the first hours to reduce consolidation of traumatic memory), but results are inconclusive.

Complementary therapy in PTSD

In addition to conventional treatments, complementary therapies can help reduce stress and improve overall well-being.

Meditation and relaxation techniques - Studies show that mindfulness meditation can help PTSD patients reduce their anxiety and improve emotional control. Deep breathing and relaxation practices can contribute to reducing cortisol levels, the stress hormone.

Yoga and art therapy - Yoga is considered an effective method for improving emotional regulation and reducing post-traumatic stress. A study conducted by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs showed that yoga can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms in war veterans.

Art therapy, which includes drawing, painting, and music, offers patients a way to express repressed emotions and process trauma in a non-verbal manner.

Animal-assisted therapy - Interaction with animals can have a therapeutic effect on people with PTSD. Therapy assisted by dogs, horses, or dolphins has demonstrated benefits in reducing anxiety and improving self-confidence in traumatized patients.

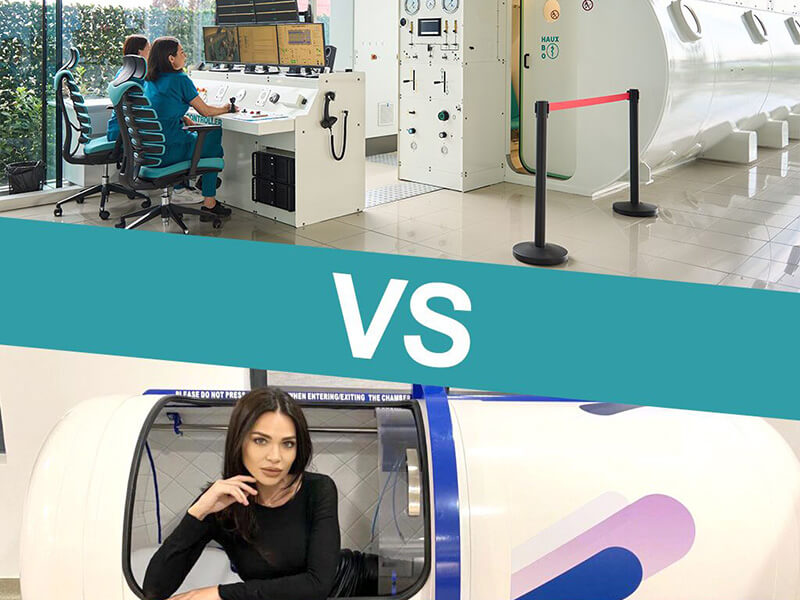

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of PTSD

In recent years, researchers have explored innovative therapies for PTSD, especially for cases resistant to standard treatments. One of these is hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). This therapy involves breathing pure oxygen at high pressure in a special chamber, a technique traditionally used for wound healing and decompression sickness, but recent studies have investigated the effect on the traumatized brain.

A controlled clinical study on veterans with treatment-resistant PTSD found that hyperbaric oxygen therapy led to significant improvements in PTSD symptoms, measured by decreases in CAPS-5 scores compared to the control group, and also demonstrated beneficial changes on functional brain imaging (increased activity in prefrontal areas, hippocampus). Specifically, after a month of HBOT sessions, patients had a strong reduction in PTSD severity (very significant statistical effect, p < 0.0001) and neuroplastic improvements were observed – better brain connections in emotional circuits.

The promising results of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) indicate significant potential in facilitating recovery of the brain affected by post-traumatic stress, by improving oxygenation and reducing neuronal inflammation, thus contributing to the formation of new neuronal connections. Although HBOT is not yet included as a standardized therapy for PTSD, scientific evidence in its favor is growing. The entire collection of studies published on the Hyperbarium clinic website provides a detailed perspective on the benefits of this therapy and the progress of research in the field.

Difference between PTSD and other similar disorders

PTSD has a symptomatology common with other disorders (anxiety, depression), which can create confusion in diagnosis. It is important for specialists to correctly differentiate PTSD from conditions that may appear similar, as the optimal treatment differs. Here are some key distinctions between PTSD and related disorders:

Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) vs. PTSD

ASD refers to post-traumatic reactions that appear immediately after the event and last between 3 days and 1 month after the trauma. ASD symptoms are practically the same as in PTSD (intrusion, avoidance, dissociation, anxiety), but the essential difference is duration: if symptoms persist >1 month, the diagnosis of PTSD is considered, and ASD is no longer applicable. Also, the diagnostic criteria differ slightly: PTSD requires a certain number of symptoms in each cluster, while ASD requires at least 9 symptoms from a total list (without imposing distribution by categories).

Another aspect is the emphasis on dissociation – DSM-5 includes in ASD symptoms such as emotional numbness, confusion, depersonalization, which if they appear immediately after trauma suggest ASD. PTSD may have a dissociative subtype, but involves the presence of all other criteria and a duration of more than one month.

PTSD vs. major depression (MDD)

Depression and PTSD are comparable because they have high comorbidity. However, there are specific symptoms that differentiate them. PTSD is closely linked to an identifiable traumatic event, while depression may or may not occur after major stress (it often has multifactorial causes, not necessarily trauma).

In major depression, flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance of traumatic memories do not occur, these intrusive and avoidance symptoms being characteristic only of PTSD. Also, depression does not present the intensity and particular type of hyperarousal from PTSD (extreme vigilance, startles, reactivity to danger cues). The depressed person may be agitated or lethargic, but not because of reliving a trauma. In depression, generalized feelings of guilt/worthlessness, persistent sad mood, and marked anhedonia are central.

But, in PTSD, there are also negative emotions, but often centered on trauma (e.g., guilt related to trauma: "it's my fault my friend died," or persistent fear "the world is dangerous"), plus pronounced anxiety related to remembering the event. It is relevant that the two diagnoses do not exclude each other – a patient who meets the criteria for both can be diagnosed with PTSD and major depression concurrently.

Differentiation between depression and PTSD is important for treatment target: in PTSD with secondary depression, treating the trauma can also alleviate depression; conversely, in a depressed person who had a minor trauma in the past but without intrusive symptoms, the focus is on antidepressant therapy.

PTSD vs. generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

Both PTSD and generalized anxiety are in the spectrum of anxiety disorders, but the nature of anxiety is different. GAD is characterized by persistent anxiety and worry without a specific object or situation – the person worries excessively about various everyday aspects (health, money, family), unrelated to a particular traumatic event.

By definition, in GAD there is no identifiable trauma that triggered the disorder, and the symptoms (tension, restlessness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, insomnia) are not related to remembering a specific experience. In contrast, PTSD is par excellence linked to a distinct traumatic event, and the person's anxiety is triggered by memories or cues related to that event.

There is another distinctive element: intrusive symptoms – flashbacks, nightmares – do not appear in GAD. An individual with GAD may have stressful dreams about their current problems, but not repetitive nightmares about a trauma. Anxious thoughts in GAD are of the type "what if... (something bad will happen in the future)," while in PTSD intrusive thoughts are "what happened is happening again" (memories from the past perceived as present). Also, avoidance (a major component in PTSD) is not present in GAD – those with generalized anxiety do not avoid situations for fear they remind them of something, but face diffuse worry.

Other differentiations

PTSD must be distinguished from adjustment disorders – if the stressor does not meet the criterion of extreme trauma (e.g., divorce, job loss) and yet significant stress symptoms appear, it is considered an adjustment disorder, not PTSD. Also, dissociative disorders can partially mimic PTSD (for example, dissociative amnesia for traumatic events), but if other PTSD symptoms are missing and the trauma is not repetitively relived, then it may be only a pure dissociative disorder.

Borderline personality disorder sometimes has emotional flashbacks and instability that may resemble complex PTSD (due to repeated childhood traumas in many borderline individuals), but in borderline the avoidance and intrusions related to a specific trauma are structurally missing, and reactivity is related more to the fear of present abandonment, not to remembering the past. The distinction of these diagnoses is made through a detailed evaluation of history and symptom patterns. A study showed that experienced clinicians can differentiate PTSD quite well from depression and anxiety based on symptom profile – with characteristic items that discriminate (e.g., "nightmares about a past event" or "I avoid talking about what happened to me" indicate PTSD, while "worry that something bad will happen" is more likely GAD).

PTSD in Romania – Challenges and solutions

In Romania, PTSD as a diagnosis has become more known in recent decades, but there are still significant challenges in recognizing and treating this disorder. One of the major problems is the stigmatization of mental health. Traditional mentality and lack of information cause people with psychological suffering (including PTSD) to avoid seeking help for fear of being judged or negatively labeled. A study on stigma in mental health in Romania shows that stigma strongly affects help-seeking – people delay or avoid going to a psychologist/psychiatrist, which leads to chronicity of problems.

Mass media sometimes maintains negative stereotypes (presenting people with PTSD either as "violent veterans" or as "irrecoverable trauma victims"), thus fueling misconceptions. At the same time, even in the healthcare system there is sometimes stigma: some patients report that their psychological symptoms have been minimized or ignored in general hospitals. The consequence is that many cases of PTSD remain undiagnosed or diagnosed late, after years of suffering in silence.

Another challenge is related to access to specialized services. The number of psychiatrists and clinical psychologists per capita in Romania is below the EU average, and in rural areas mental health services are almost non-existent. For example, there are counties without any specialized psychotraumatologist.

PTSD-specific therapies (such as trauma-focused CBT or EMDR) are not widely available in the public system; most psychologists trained in these methods work in the private sector, where costs can be prohibitive for a portion of the population. Even medication – although antidepressants are partially compensated – requires follow-up and adjustment by a psychiatrist, and visits to a psychiatrist are viewed with reluctance by some patients (again, due to stigma).

The lack of national statistics on PTSD prevalence complicates resource planning: we do not have extensive domestic epidemiological studies saying how many Romanians suffer from PTSD, but we can extrapolate from international data (~4% global lifetime prevalence) that tens of thousands of people could be affected here as well. These people may not know that their suffering has a name and a treatment.

However, in recent years steps have been taken to offer free or subsidized services for those with post-traumatic stress disorders. An example is the inauguration of the first Free Psychotherapy Center (in Bucharest, 2023), where adults, adolescents, and the elderly can receive counseling and therapy at no cost, an initiative meant to support vulnerable groups who otherwise could not afford treatment.

Also, some NGOs (including in collaboration with the Ministry of Defense or the Ministry of Internal Affairs) have assistance lines for veterans or victims of domestic violence. A recent project, PTSD Help – Dopomoha, is a free application initially intended for Ukrainian refugees in Romania, which offers psychoeducational resources about PTSD and anxiety self-management techniques.

Despite these efforts, PTSD in Romania is underdiagnosed, but not non-existent. The challenges are related to stigma, limited resources, and low awareness, but steps forward are being taken through education, training, and support initiatives. It is vital that society and the medical system recognize PTSD as a real public health problem (especially in the context of traumatic events that can affect large populations – e.g., the pandemic generated cases of post-traumatic stress in medical personnel). Through collaboration between institutions, NGOs, and the community, more effective screening and intervention mechanisms can be created, so that people affected by PTSD receive the necessary help in time.

PTSD – a global problem and the impact on daily life

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a serious, but treatable psychological condition when properly identified and managed. Although it can have a profound impact on quality of life, numerous treatments, from psychotherapy and medication to alternative therapies, have demonstrated efficacy in reducing symptoms and improving patients' overall condition. Early intervention is essential, as untreated symptoms can become chronic and can affect mental and physical health in the long term.

Early diagnosis and access to specialized treatment are crucial to prevent complications and facilitate recovery. People suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder should be encouraged to seek help and understand that their symptoms are not a sign of weakness, but a natural reaction of the brain to severe trauma. With adequate support, many patients manage to regain control over their lives.